„Laut Propaganda sollten wir das Land vor dem kapitalistischen Westen schützen. In Wirklichkeit war es kein Dienst für, sondern gegen das Volk.“

Download image

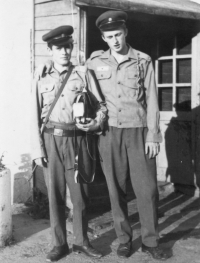

Als Jiří Bláha in der Atmosphäre der beginnenden Normalisierung den Militärdienst antrat, erwartete er nicht, dass er als Sohn eines Gewerbetreibenden aus der ersten Tschechoslowakischen Republik - und somit eine politisch unzuverlässige Person – dem Grenzschutz beitreten wird. Seine Einheit operierte in der Nähe des untergegangenen Dorfs Stoupa, auch Starý Pocher genannt. Die ursprüngliche deutsche Bevölkerung war nach dem Krieg vertrieben worden und mit dem Bau des Eisernen Vorhangs wurde das Gebiet zur Sperrzone. “Eines Tages, als wir durch den Wald gingen, sahen wir eine überwucherte Kirche. Natürlich war das Dach eingestürzt und es standen Bäume im Inneren des Kirchenschiffs, es gab noch mehr solcher Orte.” Jiří Bláha erinnert sich, dass der zugewiesene Abschnitt eher ruhig war und es nur wenige Einsätze gegen „Grenzverletzer“ gab. Er ruft sich ein ungewöhnliches Ereignis in Erinnerung. “Wir nahmen einmal eine Person fest, die nicht heraus, sondern in die Tschechoslowakei hineinfloh. Es war ein alter Mann, ein deutscher Vertriebener, er war in Böhmen geboren und wollte hier auch sterben.” Während des Dienstes am Eisernen Vorhang nahm er den abgrundtiefen Unterschied im Wirtschaftsniveau zwischen uns und den “bösen Kapitalisten” wahr, vor denen er laut Propaganda die Grenze schützen sollte: “Die Deutschen hatten schöne Häuser, Gärten, asphaltierte Straßen bis zur Staatsgrenze. Und wir liefen dort in den Sümpfen herum.” Text pochází z výstavy Paměť hranice (nejde o překlad životopisu). Der Text stammt aus der Ausstellung Das Gedächtnis der Grenze (es handelt sich nicht um Übersetzung der Biografie).