“Der Eindringling war der Klassenfeind, er musste mit allen Mitteln aufgehalten werden. Wurde der Aufforderung, stehen zu bleiben, nicht nachgekommen, war unmittelbarer Schusswaffengebrauch angeordnet.“

Download image

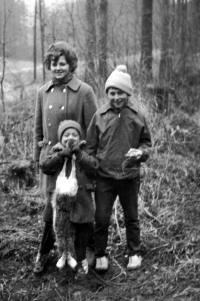

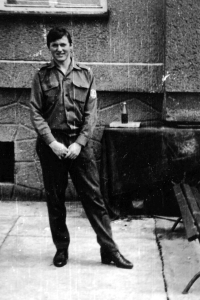

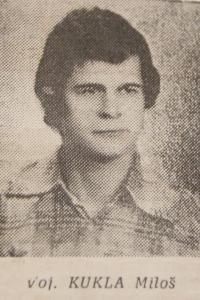

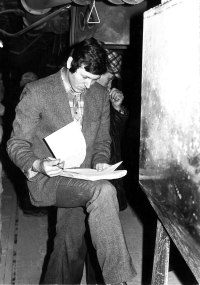

Nach Abschluss seiner Ausbildung wurde der aus Český Těšín stammende Jiří Jícha zur Grenzschutzkompanie in Zadní Chodov bei Mariánské Lázně eingezogen, also an das andere Ende der Republik, wie es zu dieser Zeit üblich war. Dort erlebte er am 27. November 1979 eine Tragödie, bei der der Eiserne Vorhang zwei Opfer forderte. Milan Myslovič, ein bewaffneter militärischer Überläufer, versuchte damals, die Grenze zu überqueren. „Der Alarm wurde zwar ausgelöst, aber niemand dachte, dass der Überläufer in dem im Landesinneren gelegenen Ausbildungsgelände landen würde. In Zadní Chodov gab es einen großen Übungsplatz, der die Staatsgrenze genau simulierte. „Myslovič dachte wahrscheinlich, es sei der Eiserne Vorhang“, erinnert sich Jiří Jícha. Die Befehlshaber schickten eine zweiköpfige Patrouille dorthin - Miroslav Plíšek und den unerfahrenen Miloš Kukla, der erst seit zwei Monaten im Dienst war - und dachten, es handele sich um „irgendeinen alten Mann“. Myslovič tat so, als würde er sich der Patrouille ergeben. „Doch dann bückte er sich plötzlich nach seiner Maschinenpistole und begann mit den Worten ‘mein Leben für euer Leben’ zu schießen. Plíšek ging in Deckung, Kukla zögerte und Myslovič schoss ihm in die Beine. Er traf eine Arterie. “ Dann verklemmte sich seine Waffe und er rannte los, in Richtung des Waldes. „Im Schock begann Plíšek wild zu schießen. Er traf den Überläufer mit einem Schuss in den Bauch.“ Den gefallenen Kukla erhob man zum „Helden, der das sozialistische Vaterland verteidigt hat“, während Myslovič zur Verkörperung des grausamen Mörders und Klassenfeindes wurde. Plíšek wurde für seine Tat ausgezeichnet, musste aber weitere eineinhalb Jahre in derselben Einheit und an denselben Orten dienen. „Sie schenkten ihm keinen einzigen Tag.“ Text pochází z výstavy Paměť hranice (nejde o překlad životopisu). Der Text stammt aus der Ausstellung Das Gedächtnis der Grenze (es handelt sich nicht um Übersetzung der Biografie).