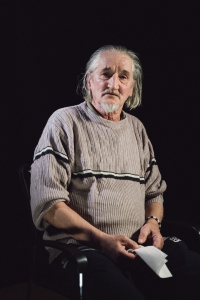

Ján Antal was born in the gulag

Download image

Ján Antal was born on February 24, 1950 in the gulag in Elgen as the son of Irena Kawashová. His mother was arrested and taken to Siberia in 1945. She was convicted to 15 years, although the real reason for her arrest has never been established. She was finally freed after Stalin’s death, in 1954. Ján was managed to get back about a year later. Irena experienced a three-month journey in a cattle wagon to Siberia, where there was a lack of food, drink and extreme cold. She lost her child when she was pregnant. After a three-month journey from Slovakia to Vladivostok, they were transported by boat to Magadan, where they were divided into labor camps. She ended up in a women’s camp in Elgen. They mostly worked outside, even in minus forty degree frosts, and mined gold. After a head injury, Irena was transferred to work inside. In 1950, she gave birth to a son, Ján, whose father is still unknown. Ján was given to a woman from a nearby village who to breastfeed him, but after two years his mother was no longer allowed to visit him because he was moved to Vladivostok. After returning to Czechoslovakia, Ján and his mother lived for a while with their grandmother in Teplička. When they managed to claim half of the house from their mother’s ex-husband, they returned to Kežmarok. Ján also went to elementary school there, he went to Kysucké Nové Mesto for high school. He was initially indifferent to the communist regime, but later felt a great aversion to it, although he did not connect it to his family history. He rebelled rather superficially, for example by listening to Karel Kryl. August 1968 found him in Hradec Králové. He divorced his first wife because she was from a strongly communist family. He spent the seventies in Prague. Later, in Kežmarok, he took care of his sick mother, who suffered from diabetes. The Velvet revolution found him in the hospital, where he was treating a broken joint. He perceived the disintegration of Czechoslovakia negatively also because he lived in the Czech Republic for a long time.