Manipulation and totalitarianism are tightened step by step and only the far-sighted can see it

Download image

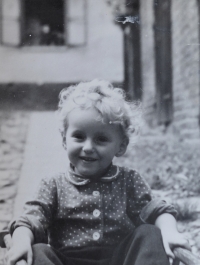

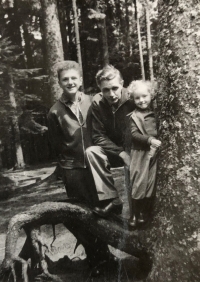

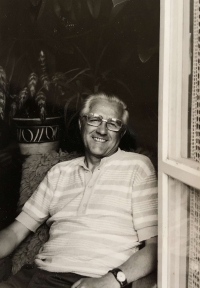

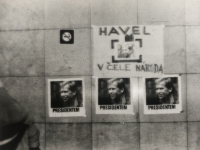

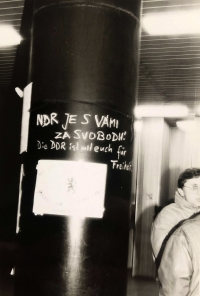

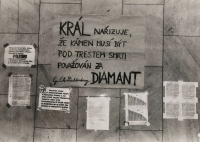

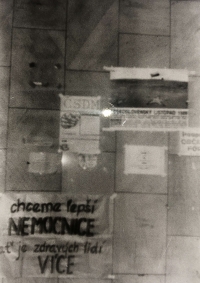

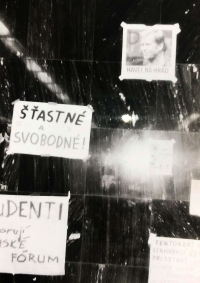

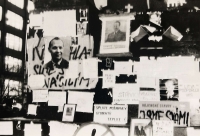

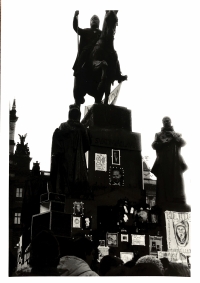

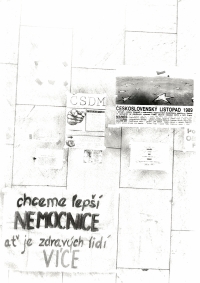

Soňa Balcárková was born on 24 December 1953 in Prague. Some of her mother Inka’s relatives were murdered in concentration camps because of their Jewish origin and their membership in the Sokol resistance. Her mother was saved from deportation to the Terezín ghetto by her father, Jan Balcárek, by marrying her during the war. The family lived in Prague, and Soňa had a brother Jan, eight years older. He had to work as a labourer for two years after graduating from secondary school because of the theatre performance titled Štafle [Stepladder] and the subsequent denunciation. Eventually he became a doctor. After the war, her parents joined the Communist Party, but because of them disagreeing with the occupation in 1968, they were expelled, i.e. crossed out, from the Communist Party during the background checks and professionally degraded. Soňa did not get the support of the grammar school to apply for university studies. She studied at secondary medical school, from where she graduated as a rehabilitation nurse. For the next ten years she worked at the clinic in Charles Square, from where she left to be able to do a two-year internship with Professor Karel Lewit. Thanks to the family´s friendship with Věra Št’ovíčková, they used to be able to get samizdat literature, Soňa copied samizdat and, in the circle of friends, she initiated fundraising campaign to support dissident families after Charter 77 was established. Her brother refused to join the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia to become a senior doctor, and emigrated with his family to the USA in 1985. From 1988, Soňa participated in anti-communist demonstrations and experienced the police massacre on Národní Street on 17 November 1989. She tape-recorded her experience during the revolutionary weeks for her brother and sent them to the USA together with photographs. After the revolution, she completed her bachelor’s degree at the Faculty of Physical Education and Sport (FTVS), where she later also had lectures for physiotherapists and continued to work in the field. Her nephew, father, and brother all died successively. Her mum lived to be 104 years old and the witness cared for her mother until her death. She was living in Prague at the time of the recording in 2021.