“Think of the chorale, o ye of little faith,” she wrote for herself in August 1968.

Download image

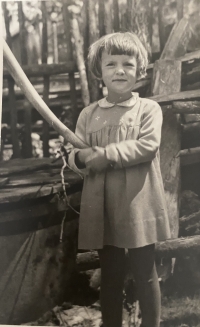

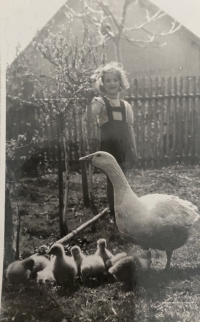

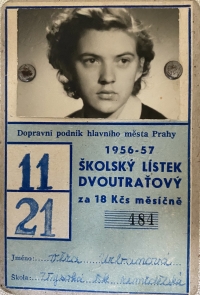

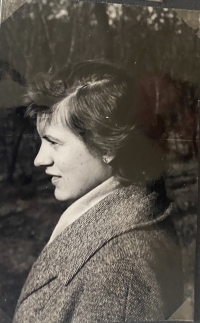

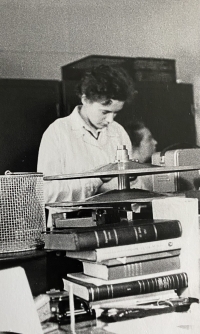

Věra Beránková was born in Prague on 27 June 1939. Her parents, Květa Urbanová and Antonín Urban, came from farms in the East Bohemian countryside, her father worked in Prague as an economic auditor She has emotional memories of the Protectorate and the 1945 air raids on Prague. Her uncle Josef Anderle joined the domestic resistance during the war; his son Jiří Anderle fled across the border to join the army. Both were caught and imprisoned in concentration camps. In early May 1945, Antonín Urban joined combat action on Prague’s barricades while Věra and her mother hid in the cellar. The communist coup affected mostly their rural relatives who were forced to join cooperatives. Věra graduated from the eleven-year school in Voděradská Street, completed high school in 1956 and joined the Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology as a medical laboratory technicia. She married Zdeněk Beránek in 1963. Daughter Monika was born in 1965. The Warsaw Pact troops invasion on 21 August 1968 caught her in the maternity ward, having given birth to their second child; her third child was born in 1975. Věra Beránková focused on her family during the normalisation period but she and her husband still went to church. In 1984 they attended a service in the presence of Mother Theresa who was visiting Prague. In 1990, as an Old Scout, Věra Beránková stood a guard of honour during Pope John Paul II’s visit to Czechoslovakia.