Be careful, intelligentsia is treacherous!

Download image

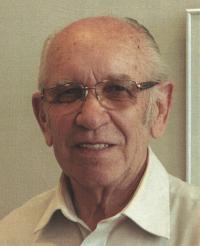

Zdeněk Bíza was born on May 8, 1936 in Rohatec near Hodonín. His father and mother were teachers and their profession had an impact on Zdeněk’s entire life. In 1942 Zdeněk began attending the elementary school in the colony Rohatec. He remembers the events of WWII through the narrative of his father; he witnessed the deportation of Jewish children and he met a teacher who was a supporter of the collaborationist group Vlajka. In April 1945 he survived the fierce fighting near Rohatec while hidden in the basement and he observed the restoration of ordinary life after the war. After elementary school he continued with his studies at the Boys’ Secondary School in Hodonín and in 1955 he completed the secondary technical school of electrical engineering in Břeclav. He worked in Hodonín, Bzenec and Moravský Písek. In 1962 Zdeněk married Marie Nováková. He has always been interested in the life of the village and since 2004 he has been writing the chronicle of Rohatec.