Love between bunkers of partisans

Download image

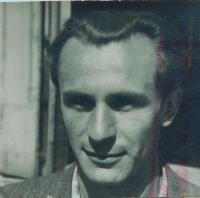

Věroslava Bojková, née Jurajdová, was born on June 26, 1926 in Bohutín in the Šumperk region. During World War Two, in 1942, her brother Mnislav was drafted to the Todt organization and sent to work in Ukraine. During his only short leave when he got home, Mnislav brought some friends with him, and one of them was Václav Bojka. It was at that time when Věroslava got acquainted with him. Václav then kept visiting her regularly, walking from Rovensko which was seven kilometres away. He lived in this village and he was also active in the local illegal anti-Nazi group, which was organized under the National Association of Czechoslovaks Patriots. In April 1944 the Gestapo came to arrest Václav Bojka. He escaped through the window, he joined the partisans and he was hiding in forests until the end of the war. However, he secretly kept visiting his beloved Věroslava. She was handing over messages to the partisans, bringing them food and repairing clothes. Václav nearly lost his life in one of the last clashes of the war, during a fight for an electric switchboard station in Ráječko. A shrapnel from a grenade missed his heart only by several millimetres. Fortunately he survived and in 1946 Věroslava and Václav married. Their daughter Věra was born in 1948 and their daughter Miroslava three years later. Václav Bojko died one month before their fiftieth wedding anniversary in 1996. In 2017 his wife Věroslava Bojková still lives in Bohutín.