I say what I think, and that’s where the trouble comes from

Download image

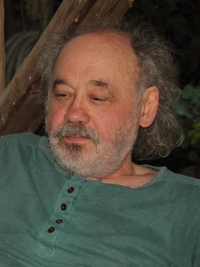

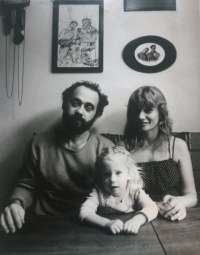

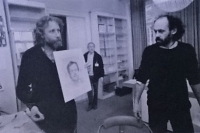

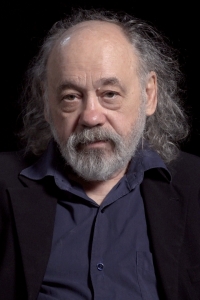

John Karel Bok was born on October 24, 1945. His parents were Czechoslovak RAF pilot Bedřich Bok and Englishwoman Florence Mary Spence, who left her homeland for Czechoslovakia with her father after the war. The family was persecuted and moved from place to place in the 1950s. The father joined the Communist Party and was repeatedly expelled, and the State Security forced him to cooperate in provoking those planning to emigrate. His parents divorced in 1956, and John Bok trained as an electrician and worked in various manual occupations. In 1966, his mother and sister decided to return to their homeland. During the totalitarian era, John Bok was mostly employed manually, working for nine years as a train driver on the construction of the Prague underground. He signed Charter 77, was involved in the production and distribution of banned publications, and smuggled foreign literature and magazines from his travels to the West in the 1980s. At the time of the Velvet Revolution, he organised Václav Havel’s security detail. After the Velvet Revolution, he worked for three years in the state administration. In 1994 he founded the Solomon Association with the writer Lenka Procházková, which aims to defend the rights of the unjustly prosecuted, to improve prison conditions and to seek presidential pardons for people affected by miscarriages of justice. John Bok is an activist who is known for holding hunger strikes, most recently for the resignation of Stanislav Gross. He is the father of five children and lives with his wife, artist Jitka Boková.