One should be tolerant of those closest to him and merciful to others

Download image

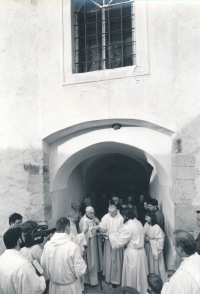

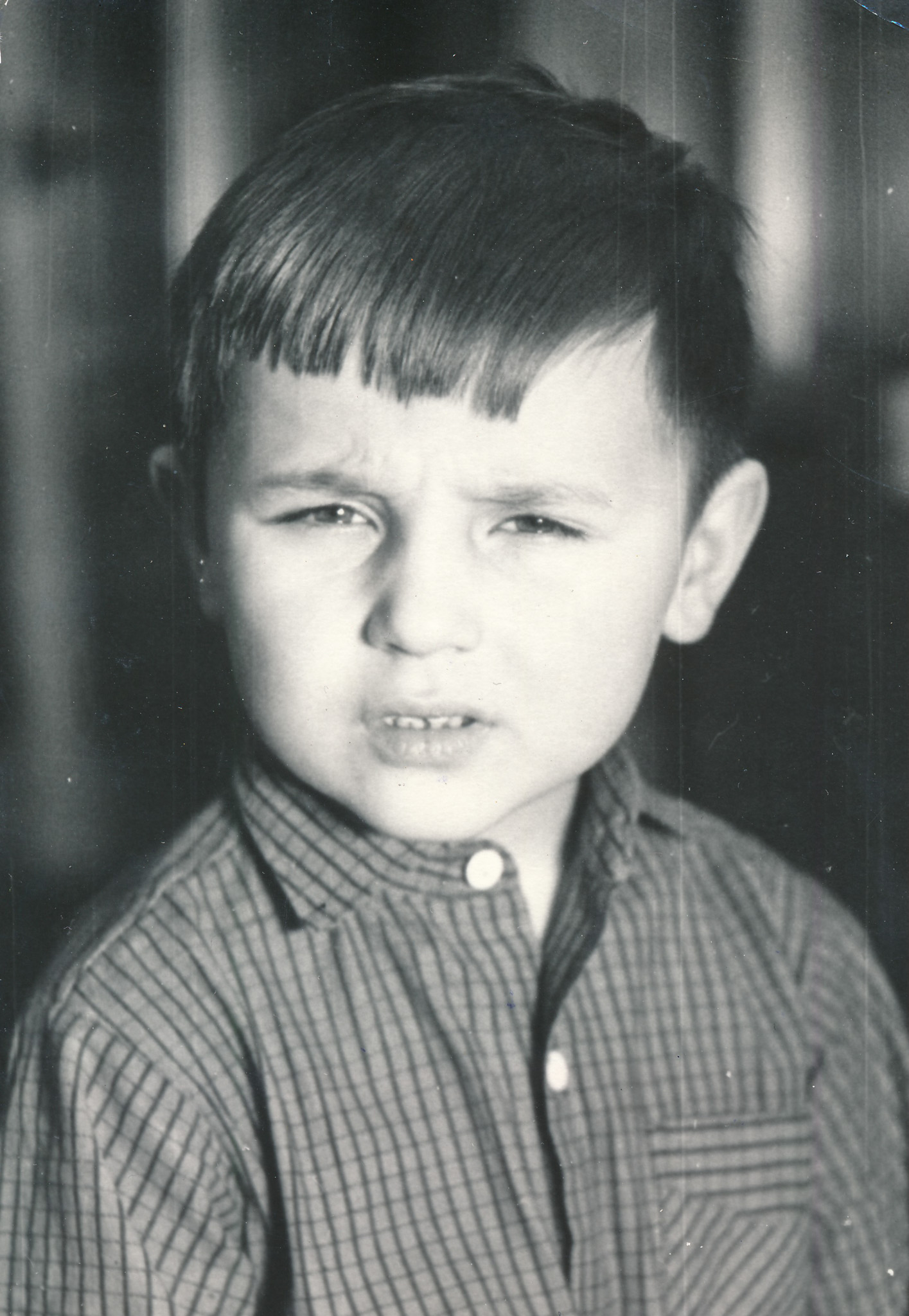

Richard Borovský was born on 9 September 1958 as the middle of three children. His father František came from Slovakia and was imprisoned in Jáchymov for four years in the early 1950s. His mother Bedřiška came from a farm in Hradec nad Svitavou and the communists had forced her parents to join a farm cooperative (JZD). The family lived in Kuwait in 1967-1972, as his father, a radiologist, helped build a hospital and his mother taught first stage in a Czech school. The family would go back to Czechoslovakia for the summer, but the Warsaw Pact troops invaded in August 1968 and they had trouble returning to Kuwait because there were no flights. In Czechoslovakia, Richard Borovský finished primary school and entered the High School of Economics in Hradec Králové, graduating in 1977. He then spent four years at the University of Economics in Prague before voluntarily leaving in 1981. He completed his military service with the road building corps in Prague and around. In the 1980s he attended apartment seminars and joined the Prague underground. He worked briefly at the post office where he was in charge of assigning mail cars to the right trains at the main station. Two years later, friends got him a job as a pumper at Vodní zdroje (water sourcing company) where he worked outdoors and was free. In 1986, he founded the men’s order Regula Pragensis, which is still in operation today, with his friends from Vodní Zdroje Viktor Faktor and Emanuel Mařík. He participated in the publication of the Lázeňský host samizdat magazine in the late 1980s. He took part in protests in Prague during the Palach Week and in November 1989, and afterwards he and friends ran a bookshop and antiquarian bookshop in Jilská Street and a café in Lucerna. In the early 1990s, he and his friends founded a mail-order service to send Czech literature abroad, through which they still sell Czech literature primarily to Slavic studies departments at universities around the world. He lives in Prague and has an adult son.