When they thought they had something on me, they didn’t call me ‘comrade’, they called me ‘Mr. Brož’

Download image

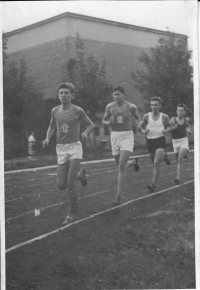

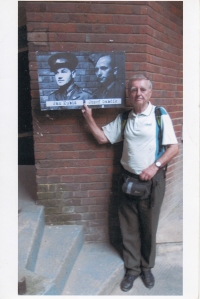

Radovan Brož was born on 29 September 1936 in Pardubice to a postal clerk and a housewife. Both parents were involved in sports, his father contributed texts to a sports magazine. They also encouraged their two sons to play sports. Radovan ran medium distances and after high school continued his studies at the Faculty of Physical Education. He became a professional athletics coach in Pardubice and stayed in this position until 1992. His childhood was marked by the Second World War, he experienced three air raids on Pardubice, hiding in a cellar and finding a bomb shell in his kitchen at home. As a coach, he was contacted twice by the State Security, once in 1961 with a request to inform on him, the second time when the Centre for Youth Sports in Pardubice was founded. In 1972, after employment checks, his passport was revoked and he was not allowed to travel abroad for 14 years. After his passport was returned, he visited Cuba, North Korea and Canada on business, where he met an expatriate friend and looked into ´68 Publishers. His elder daughter Veronika was in trouble at university for photographs from a trip to Leningrad. In the mid-1980s, he was pressured to administer anabolics to his charges, which he refused. After his retirement he devoted himself to the history of athletics, cycling, tennis and football in Pardubice. He has held a number of positions in Pardubice athletics and is a lifelong fan and connoisseur of Pardubice.