I was to be expelled from the Party and I did nothing to save myself

Download image

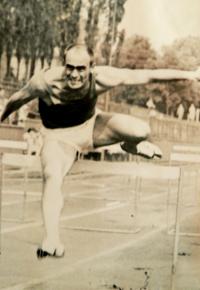

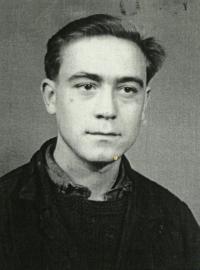

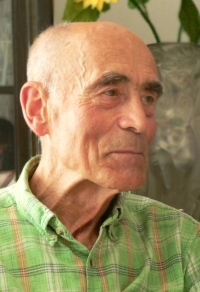

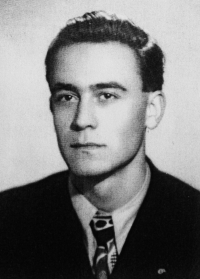

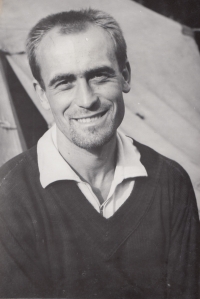

Josef Bubeník was born April 24, 1934 in the village of Dubňany in the region of Moravian Slovakia. As a child from a poor family he had certain advantages in the time after the communist takeover of power in February 1948. He had to work very hard to complete his vocational training as a fitter and then at secondary industrial school. Since his early years he has been an avid athlete, and after graduating from the secondary school, he wished to devote his time completely to sport. For this reason, he chose to study at the Institute of Physical Education and Sport. It was at this facility where he was advised to join the Communist Party in 1957. When his classmates offered him membership in the Party, he turned the invitation down at first, but he became convinced after several days with their insistence that people with pristine reputation needed to get into the Party in order to outnumber the rogues who were already there.He worked as a teacher at the Faculty of Physical Education in Ústí nad Labem, and during and after the invasion of the Soviet army on August 21, 1968 .He was, as a Party member, invited to become a member of the Communist Party committee at the faculty. The committee immediately began discussing the issue of what stance the faculty ought to take towards the so-called revivalist period (which later came to be called counter-revolutionary), and who would have to be expelled from the faculty. Bubeník came up with his own amendatory suggestion to the committee’s decision: he proposed to lower all proposed academic penalties by one degree in severity. His proposal was naturally not approved. Because Bubeník openly voiced his disagreement with Soviet army’s invasion in front of the committee and failed to denounce the revivalist movement, he was expelled from the faculty and from the Party. He then taught at a secondary school of economics, and later he worked for the railways. Besides this he tried to work with children as a sports coach, but the regime repeatedly prevented him from this activity. In 1989, his son Jan Bubeník formed a student strike committee at the Faculty of Pediatrics of Charles University and became its chairman. With other student leaders Martin Mejstřík and Šimon Pánek, he became one of the leading figures of the student movement.