We wanted to live in truth and equality. That’s why we fled.

Download image

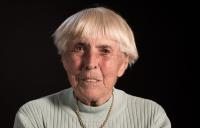

Věra Čáslavská was born on 18 January 1934 in Chrudim, into the family of the lawyer Vilém Novák. Her grandfather Eduard Kudrnka was a well-known figure in Chrudim, he was the town doctor, he helped poor people and was very popular. In the 1950s he died after being interrogated by State Security. That was one of the moments that built up a strong hostility towards the Communist regime in the witness. Her stance was reinforced by her husband Jaroslav Čáslavský, whom she married when she was eighteen. As a secondary-school student, Jaroslav was asked by a teacher to hand over some photocopied documents to a person sitting in a car at a certain place. He recognised the person as Milada Horáková. The documents contained information that a high-ranking Communist functionary had served as a warden in a concentration camp. When Milada Horáková was executed and following the massive political trials, Jaroslav Čáslavský feared for his life, as he found himself under State Security surveillance. In 1965 the Čáslavskýs received permission to go on a trip to Austria, and they took the opportunity to emigrate. They left their eight-year-old daughter, whom they had told about their plan, in the care of her grandmother in Czechoslovakia. From Austria they travelled to the United States. It was not until 1968 that they succeeded in obtaining permission through friends and officials for their daughter to come and join them. They settled down in the United States and became respected experts in their field of chemistry. After 1989 they began visiting Czechoslovakia, which Věra still considers to be her homeland.