The mayor takes care, the chairman presides

Download image

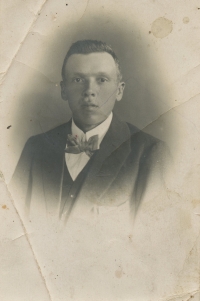

He was born on 28 October 1938 in Vysoké Chvojno. In his story he mentions the bloody course of the May 1945 uprising in nearby Holice. As the son of a farmer (and the village mayor) who farmed 14 and a half hectares of arable land, he was unable to study at his chosen school despite his good grades. He trained as an operating chemist in the petrochemical industry and joined Parama Pardubice, where, apart from basic military service, he spent his entire professional life. After the vetting process in 1970, he lost his management position and had to join a health-threatening barisol operation called Gulag Paramo. After eight years he became seriously ill, but after successful treatment he returned to Paramo again, albeit in a different department. After 1989 he built up the marketing department and became a specialist in Parama asphalt products. He retired from this position in 2002. In his home village of Vysoké Chvojno he was mayor for two terms after November 1989. In 2021, he and his wife lived in Vysoké Chvojno.