We knew we didn’t want to live in it any more, we had had enough

Download image

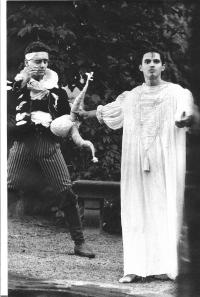

Pavel Chalupa was born on 31 August 1963 in Teplice as the second of three children. Both his parents and later his elder brother were Communists. After attending primary school in Varnsdorf, he trained as an electromechanical technician and then completed an evening course at the Secondary School of Electrical Engineering in Prague. Throughout the time of his training, studies, and apprenticeship, he longed to become an actor, and so he sought out artistic environments; he worked in dubbing and as a film extra. He also had the opportunity to act at the factory club of his employer, ČKD Semiconductors, where he led and directed an amateur theatre group. Later, he worked as a student actor at the regional theatre in Uherské Hradiště. After two failed attempts, an appeal finally gave him a successful application to study at the Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (DAMU) in 1986. During his studies, he was one of the politically active students - he took part in demonstrations against the regime, public debates, protest petitions, and in spring 1989 also the dissolution of the Theatre Faculty’s branch of the Socialist Youth Union. On 18 November 1989 he actively participated in the formation of the school’s strike committee and the declaration of a student sit-in strike to a gathering of theatre employees at the Zdeněk Nejedlý Realistic Theatre in Prague, where he read out - as the first student to do so in public - the Declaration of DAMU Students as a Call for a Protest Strike. From the outset of the revolution, he was a prominent member of the strike committee; he participated mainly by organising the so-called “beauty rides” (after the eponymous excursions of Hussite fighting bands outside the country in the 15th century - trans.) outside of Prague, in which students and celebrities brought news of events to factory workers etc.; he also participated in the discussions with audiences at the National Theatre that replaced regular performances. In 1990 he concluded his studies at the Theatre Faculty and started his first professional acting roles. Besides acting, he later also worked as a director, dramaturge, scriptwriter, manager, editor, and producer in television, film, radio, and dubbing. He founded the global Romani festival Khamoro and the Jewish culture festival Nine Gates; he is the author and implementer of the Lusting Train project, the founder of the Centre for Genocide Studies in Terezín, and the co-author of the Magnesia Litera literary award. Pavel Chalupa lives and works in Prague.