Collectivisation turned farmer owners into dependant serfs

Download image

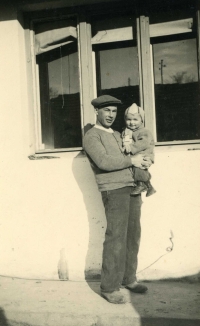

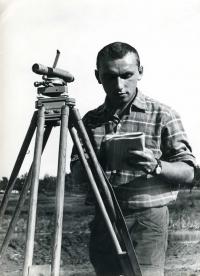

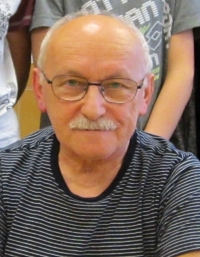

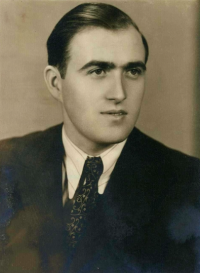

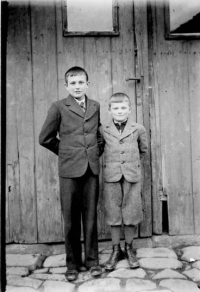

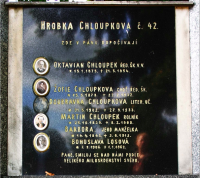

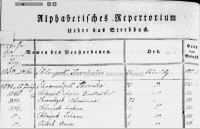

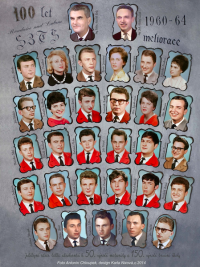

Antonín Chloupek was born on 24 June 1944 in Střelice near Brno. His family had been farming here since at least the 17th century, when the first local register mentions them. His father Antonín Chloupek Sr. was the last farmer from the village to resist collectivisation. He did not sign the application form until 1958, when he was threatened that his sons would not be allowed to study or apprentice. In 1959, the wirtness was admitted to the agricultural secondary school in Roudnice nad Labem. Here he discovered his lifelong passion for photography. After a year of work in the mines in Karviná, he joined the basic military service. He applied unsuccessfully to be admitted to Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU) twice. From the beginning of 1968 he lived in Prague, where he worked at the Polygrafia printing house. He spent 21 August 1968 with his camera in the streets of Prague, documenting the occupation. From 1969 he worked as an assistant art director at Barrandov film studios, where he witnessed the normalisation checks. After his marriage in 1976, he moved to Jihlava, where he found employment at the Fotografia cooperative company, and in 1992 became a private photographer.