There are many positives as well as negatives; personally I see more positives - we can move freely

Download image

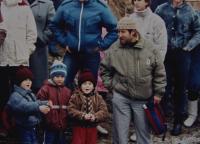

Jozef Chrena was born on March 10, 1948 in Moravský Svätý Ján. He was growing up together with his three brothers. In their family there was natural resistance against the communist regime, which beside other facts originated also in the reality that in 1950s the regime confiscated their only cow. Since his childhood Jozef Chrena felt to be artistically talented and after the elementary school he wanted to continue his studies at famous Bratislava’s School of Art Industry (today it is the Jozef Vydra’s School of Applied Arts in Bratislava). However, he wasn’t accepted. Since he didn’t have chance to do art professionally, after finishing the secondary school he worked in various professions; during the second half of 1980s he was an ambulance driver. Besides his regular work, in his privacy, he devoted himself to landscape painting. During the revolutionary days of November 1989 Jozef Chrena decided to help to fight for freedom. In Moravský Svätý Ján in a public place he posted a self-painted poster informing about the upcoming nationwide general strike, demand of free elections and about an end of the communist tyranny. In the following days and weeks, also despite of telephonic and written threatening of physical liquidation, he was engaged in organizing local manifestations and preparations for establishing the public party with democratic program. Together with his friends they decided to organize a manifestation march towards the Morava River, where they wanted to carry out a friendly meeting with citizens of the neighboring Austrian village Hohenau. After solving many problems, on December 30, 1989 they managed to organize a March of Freedom, which on a Slovak side attended approximately 15 000 people. As majority of former Czecho-Slovakia’s citizens, also Jozef Chrena was hoping for better development of future after the year 1989. In spite of various disappointments in events that happened during the following years, he is still convinced that the fall of the communist regime and gaining back freedom has been a great benefit for the society. Today Jozef Chrena is a respected painter.