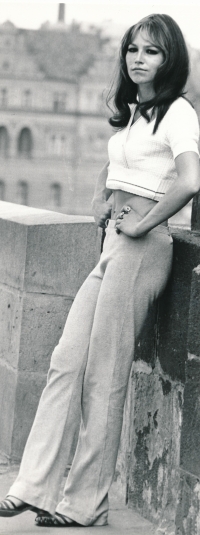

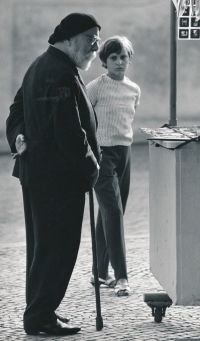

Back in the day, people were flattered when someone photographed them on the street. After the revolution, they would get annoyed.

Download image

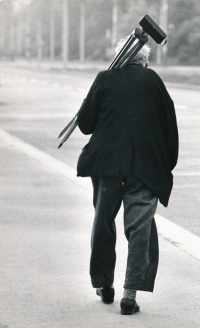

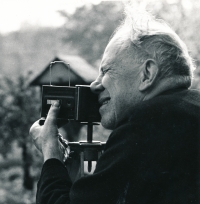

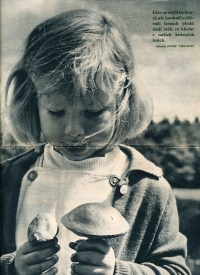

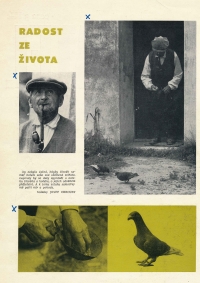

Josef Chroust was born on the 26th of January in 1935 in Hradešín in central Bohemia as the third child of Antonie and Václav Chroust. His mother was schooled a dressmaker, his father was a barber but neither did the job, they were smallholders. Josef remembers the WWII in Hradešín where he went to school and later on, to the Boy Scouts. The Boy Scouts were banned by the Communists in the 1948, though. Václav wanted to be a gamekeeper but he was not admitted to a forestry school for political reasons – his parents, as smallholders, were not preferred by the ruling regime. Václav thus went into apprenticeship in the Elektročas [Electro-Time] factory, later on, he attended evening courses and graduated from a trade school. Then, he worked in the Tesla factory as a production dispatcher. After ten years, he switched employers and worked in the Laboratorní přístroje [Laboratory Equipment] company as a coordinator of technical standardisation. At the age of 58, he was awarded an exceptional early retirement payout due to closure of the company. Aside from his day job, he was an amateur photographer and filmmaker. For two years, he attended the Popular Academy where he studied filmmaking and in the 1960’s, he was offered external collaboration with the Czechoslovak Television. This was however paid so poorly that Václav dropped this sort of filming and devoted his time mostly to photography. Until the early 1990’s, he published hundreds of photographs in various periodicals. He photographed mainly street life, architecture and nature. He also wrote short commentaries for a satirical weekly. He was not interested in political themes. At the beginning of the 1990’s, he retired. His latest photographs date back to that time.