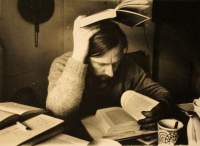

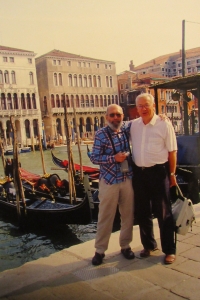

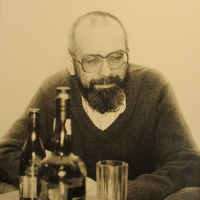

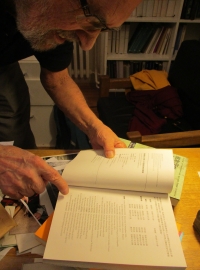

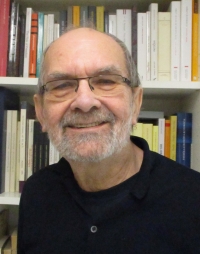

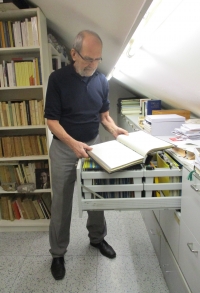

We didn’t do philosophy as a job but as a real thing

Download image

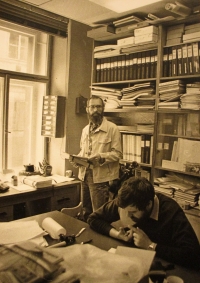

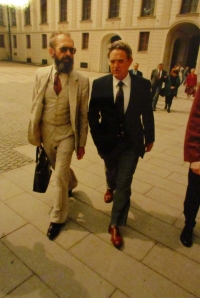

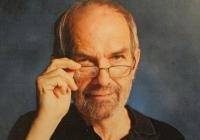

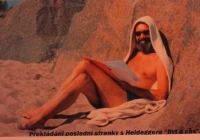

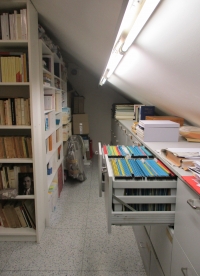

Ivan Chvatík was born in Olomouc on September 15, 1941. He graduated from nuclear physics at the Czech Technical University in Prague. After being briefly employed at the Department of Logic at Aritma, he worked for more than twenty years as the head of the Technical Department of the Computer Centre of the Machine Technology Factories in Prague (1967-1989). He was in charge of the operations of the Swedish computer Datasaab. At the same time he devoted himself to philosophy. From autumn 1968 the witness attended Patočka’s lectures at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University, and a year later he became Patočka’s external research candidate. When Patočka was forced to leave the faculty in 1972, Ivan Chvatík initiated the organising of home seminars in Patočka’s flat, together with his lecture series “Care of the soul” that is now known as Plato and Europe. After Patočka’s death in March 1977, he and his friends saved the philosophers writings, which they gradually worked on releasing in samizdat. They managed to publish 27 volumes in blue binding, now called the Archival Series of Jan Patočka’s Works, before the Velvet Revolution. In the 1980s, he provided translations and exile publishing of Patoček’s works. He was an active participant and organizer of residential philosophical seminars, and was engaged in the translation of Martin Heidegger’s work. Immediately after the revolution, together with Pavel Kouba, he founded the Jan Patočka Archive. In the 1990s, he became involved in founding the Central European University in Prague. He continues to publish Patočka’s Collected Writings, the concept of which is partly linked to the Archive File, and he takes care of Patočka’s legacy. He was awarded for his work by Charles University, the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic and the Vision 97 Foundation. In 2021, he continued to work as the Deputy Head of the Archive, Jan Patočka.