The best way to subdue an individual is to make him dependent on gifts

Download image

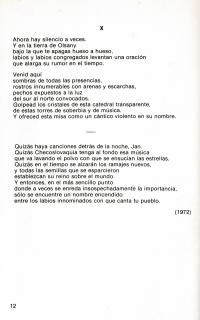

Ángel Cuadra was born in 1931 in Havana, Cuba. He comes from a modest family. He studied at the University of Havana and opposed the regime of Fulgencio Batista. He emphasizes the influence of his mother, who was a member of the Authentic Cuban Revolutionary Party. In 1957 he was one of the founders of the Renuevo Literary Group. Having graduated in Law he practiced as a lawyer until 1967. Disappointed with the direction taken by the Revolution of Fidel Castro, he wrote for a magazine critical of the Castro government. When the first persecution against his person began, he rejected the offer of asylum from the Embassy of Uruguay. In 1967 he was arrested, accused of conspiring against the regime, and imprisoned for 15 years. In prison he dedicated himself to the clandestine publication of literary texts of political prisoners. He was named an honorary member of the PEN Club of Sweden, and his case became famous abroad. Thanks to this, in 1981 he was elected prisoner of conscience for the month of March. When he was released, he traveled to Sweden and Germany, the countries that had most pleaded for his freedom. In 1985 he emigrated to the United States, where he was reunited with his family. He graduated in Hispanic Literature at the University of Florida and worked there as a professor of Modern Languages. He received several poetry prizes and his poems have been translated into several languages.