We supported Czechoslovak dissent, but it was not illegal

Download image

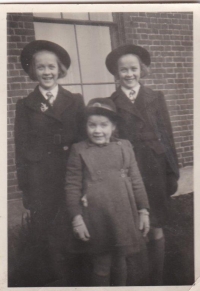

Barbara Day was born on June 9th 1944 in the United Kingdom, as the third daughter of a schoolmistress and a Church of England priest. She spent her childhood in a rectory house in Sheffield and in a boarding school, after that she went to Sheffield Girls High School and graduated from The University of Manchester where she studied Drama. From 1965 to 1966, she lived in Czechoslovakia on a scholarship; she also witnessed the Warsaw pact invasion of August 1968 She had been working in theatres in London, in Bromley, in Stoke on Trent and in Bristol, where she organised the Bristol Czechfest, a festival of Czech culture, in 1985. Since the mid 80s she had been working with the Jan Hus Educational Foundation and she took part in organizing seminars and lectures by Western academics and intellectuals in Czechoslovakia. She has been awarded the Order of the British Empire member class, she also received a memorial medal of the President of Republic, Václav Havel.