With a little help from my friends...

Download image

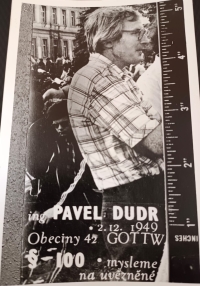

Pavel Dudr was born on December 2, 1949 into the family of a secondary school teacher, who was banned from teaching in 1958. Pavel Dudr attended a secondary technical school, and before the onset of normalisation he was accepted to study at the Faculty of Mechanics of the Technical University in Brno. After graduating with an engineering degree, he found employment in a shoe factory in Zlín. In the late 1970s he began distributing illegal literature and publishing his own illegal magazine, Infoch. He was informed upon in autumn 1985, and arrested. Thanks to his friends, the news of his arrest was broadcasted by foreign radio, the Voice of America. This international attention assured Dudr better treatment in custody, an early release in 1986, and probably also influenced his trial. Although he had to wait years for the trial, in spring 1989 Pavel Dudr was given a suspended sentence. After the Communist regime dissolved, Pavel Dudr founded a successful company, which is now managed by his descendants.