One does not need to see life’s trials and obstacles as tragic

Download image

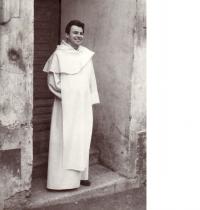

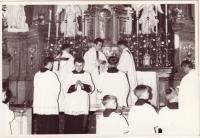

Cardinal Jaroslav Dominik Duka OP was born on April 26, 1943 in Hradec Králové. He comes from a military family. His father František Duka served in the Government Army during the war; he deserted and he went to Great Britain, where he joined the Czechoslovak foreign army. He served as an armourer in № 311 Czechoslovak Bomber Squadron of the Royal Air Force and after 1948 he was imprisoned in communist Czechoslovakia together with many other soldiers who had fought on the western front. Jaroslav completed an eleven-year school in Hradec Králové. Due to his personal profile he was not allowed to study further and he thus began working in the ZVÚ factory, where he apprenticed as a machine fitter. It was only in 1965 when he was admitted to the Sts. Cyril and Methodius Faculty of Theology in Litoměřice. He graduated in 1970 and he was ordained a priest. In 1970-1975 he served as a priest in western Bohemia in the parishes Chlum Svaté Máří, Jáchymov and Čížkov. In 1968 he joined the Dominican Order and he adopted his religious name Dominik. When the West Bohemian Regional Administration cancelled his state authorization for serving as a priest in 1975, he found a job as a draughtsman in the Škoda factory in Pilsen. Together with other Dominicans they established a small secret Dominican community in a house in Revoluční Street in Pilsen. Dominik was also involved in organizing secret education for members of the Order and in publishing and disseminating samizdat religious texts. In 1981 he was sentenced for this activity to fifteen months of imprisonment for the offence of disrupting the state control over churches. He served his sentence in the Bory prison in Pilsen. In 1986-1998 he served as the provincial of the Czechoslovak Dominican Province. In 1998-2009 he was the bishop of Hradec Králové. In 2010 Pope Benedict XVI appointed him the archbishop of Prague and in 2012 he was appointed as a cardinal. In 2022, he was replaced in the office of Archbishop of Prague by the current Archbishop of Olomouc, Jan Graubner.