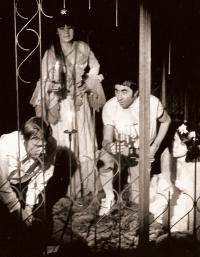

If we hadn’t kept things going there with Kladivadlo theatre, if we hadn’t been there, then obviously no theatrical group would have appeared in Ústí. There would have been no Theatrical Studio.

Download image

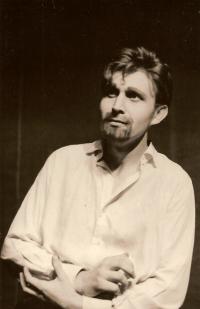

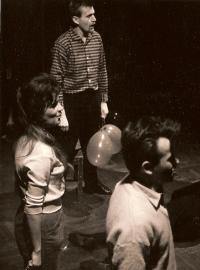

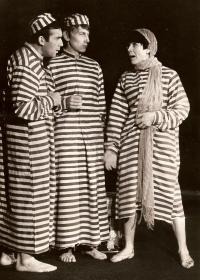

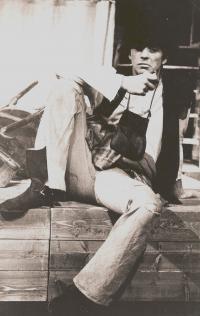

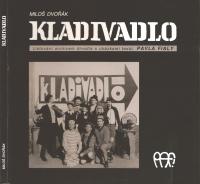

Miloš Dvořák was born on the 29th of January 1930 in Smiřice. He completed grammar school in Hradec Králové. He was then issued the place of a primary school teacher in Broumov. His parents were amateur actors in Smiřice and he himself had taken an interest in acting already as a child. In 1958 he founded the amateur theatrical group Kladivadlo in Broumov, together with the playwright and director Pavel Fiala. The group moved to Kadaň in 1963. Kladivadlo also achieved much success at prestigious theatrical competitions and festivals, and after moving to Ústí-upon-Labe in 1965, turned professional. During the normalization, the name “Kladivadlo” was banned and Pavel Fiala was forced to leave. Miloš Dvořák reassembled the group in 1972 under the name The Theatrical Studio (Činoherní studio). He worked there as operations manager until 1990, closely cooperating with art directors Jaroslav Chundela, Ivan Rajmont, Pavel Pecháček and Petr Poledňák. The Theatrical Studio soon became a progressive phenomenon throughout Czech culture. After the Velvet Revolution, Dvořák left for Prague, where he joined the Realistic Theatre (today’s Švandovo divadlo), before moving on to the National Theatre, with which he still cooperates in his retirement.