To appreciate every moment...

Download image

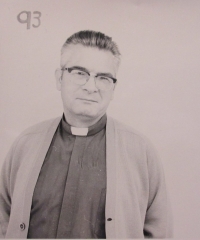

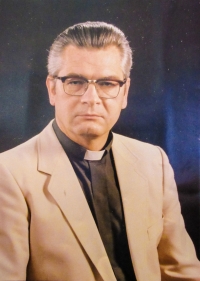

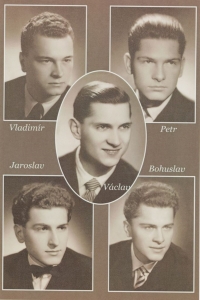

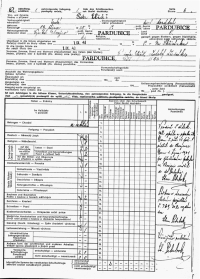

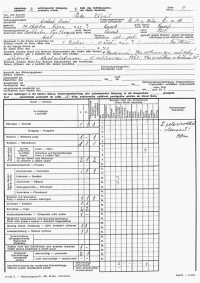

Bohuslav Eliáš was born on March 14, 1937 in Pardubice as the fourth of five sons of Vladimír and Anna Eliášovi. His father, an officer of the Czechoslovak Republic army in reserve, died on May 8, 1945 in a collision with a German armored car. Shortly afterwards, his mother and the children moved to Liberec, where his uncle Jaroslav provided them with supportive environment. All five brothers soon became passionate about music. After finishing secondary grammar school, Bohuslav Eliáš thought about entering the conservatory, but in the end, he kept music just for fun and graduated from the Faculty of Civil Engineering. He enjoyed the joys of music abundantly after returning from military service, when he became a choirmaster of the church choir for many decades, later an external member of the Liberec theater and his own dulcimer band. In 1962, he got married and had three children. During the period of political relaxation, he founded a Catholic Scouts club, which, after scouting was banned again, he managed to integrate under TJ Ještěd. In the 1970s and 1980s, he supported the activities of illegal Franciscan communities and participated in spiritual activities not authorized by the state. From 1978, he worked at the secondary school of construction in Liberec. There, in November 1989, he became the initiator of protest actions that helped stir up the Velvet revolutionary events in Liberec. In 2023, Bohuslav Eliáš lived in Liberec.