Per aspera ad astra - through hardships to the stars

Download image

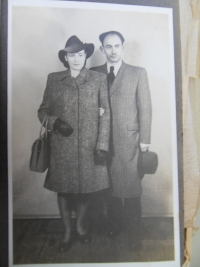

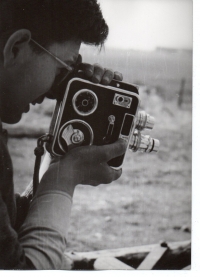

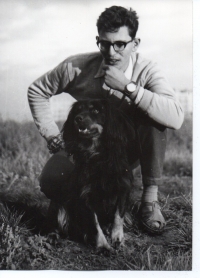

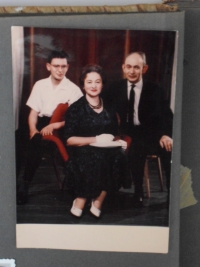

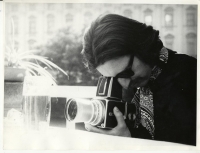

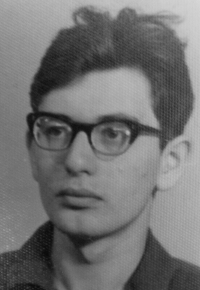

Harry Farkaš was born on May 22, 1947 in Bratislava, but his parents lived in Děčín, in Bohemia. His father, Bernard Farkaš, was a Jewish rabbi and his mother was a teacher. In 1957, as a little boy, Harry witnessed how the State Security arrested his father and searched their flat. His father was sentenced for anti-state activity to two years of imprisonment. After the release from prison, in 1958 the whole family moved to Karlove Vary, where the father continued to serve as a rabbi. At last, they settled down in Prague. Harry Farkaš attended grammar school; he was interested in photography and filming. In 1964 his family was granted permission to move to Israel, however, only Harry left and stayed there for two years. His parents wanted to go to Germany, where his father was offered a job of a rabbi in Aachen. Since it was impossible for Harry to graduate in Israeli grammar school in such a short time, he moved with his parents to Aachen. He learned German language and graduated from school of film and photography in Cologne. For forty years he worked in public service broadcasting as a cameraman, he filmed reportages in Germany as well as abroad and took part in many television productions. He visited Prague several times prior to 1989, and after his retirement he likes to return to this city more often, even for a longer time. Although his parents lived to older age, they had never returned to Czechoslovakia.