I don’t count the blows - when something needs to be done, I start running

Download image

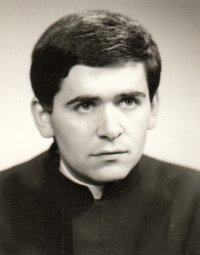

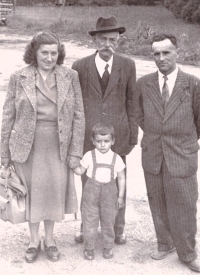

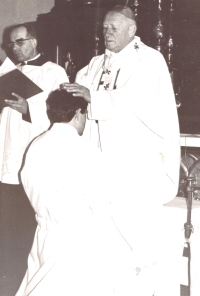

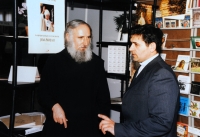

Jan Fatka was born on 14 May 1955, the only son of Jan Fatka and Ludmila Fatková. He spent his childhood on the family farm in Žernovice near Prachatice. After graduating from the secondary school of agriculture in Dub near Vodňany, he started his basic military service, during which he decided to become a priest. In 1977, before entering the seminary in Litoměřice, he joined the illegal Carmelite Order. After receiving his priestly ordination at the hands of Cardinal Tomášek, he served in the parishes of the České Budějovice diocese, where, with the help of his friends, he tirelessly set about repairing neglected church buildings. After the Velvet Revolution, he participated in the renewal of the Carmelite Order, under whose auspices he founded the Carmelite Publishing House, which he headed for 22 years. Since 2013 he has worked as a chaplain in Prague hospitals.