State Security officers would come to cry in my office

Download image

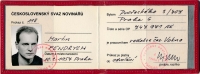

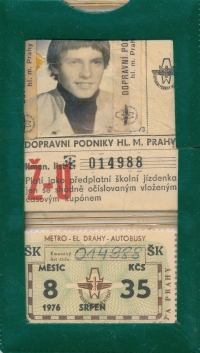

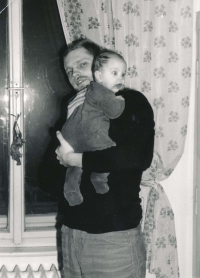

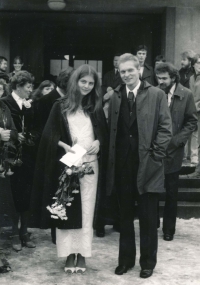

The publicist and former Deputy Minister of the Inferior Martin Fendrych was born on 10 January 1957 in Prague. Both his parents were persecuted by the communist regime and could not do their original jobs; his father, who had graduated from law, worked as a bus driver. At the end of elementary school, Martin won a competition to study at the lycée in Dijon, but he did not receive a recommendation from the street committee, so he studied at the Sports Grammar School in Přípotoční Street. The background of the Evangelical congregation in Střešovice and mainly the personality of pastor Jaroslav Vetter largely contributed to his spiritual journey. Having passed his Secondary-school leaving exam, he studied Air engineering at Czech Technical University. However, he left the studies after three years and he made his living manually - as a loader at the airport, a window washer, a hospital attendant at the Under Petřín Hospital or a stoker in a boiler room. He was friends with people with underground background and he was mainly interested in and inspired by underground culture in the 1970s and 1980s. He helped copying illegal Lidové noviny (People’s Herald), he also participated in spreading of samizdat Vokno magazine (Window magazine) and Revolver Revue. In 1980 he married his wife Alena and they had for children together. He started to work as a spokesperson in the Federal Ministry of the Inferior in 1990 and he became Deputy Minister of the Czech Minister of the Inferior Jan Ruml after the break-up of the Federation. He kept working as Deputy until 1997. He has been working in the media since that time, he has worked among others for Respekt and Týden magazines (Respect and Week magazines) and he has also freelanced for Czech Television and Radio. He has worked as a commentator for the news website Aktualne.cz. until now. He has published several novels and books with autobiographical themes, such as Jako pták na drátě (1998), Samcologie (2003), Slib, že mě zabiješ: blogoromán (2009) and the newest one Šílenec (2021).