As a kulak daughter, I was not allowed to study

Download image

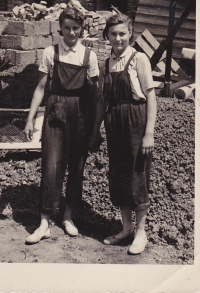

Berta Fišarová, b. Plevová, was born on September 7, 1941 in Velká Losenice near Žďár nad Sázavou. She was the firstborn child of the peasants Josef and Pavlína Plev, who owned rather a larger farm. In the 1950s, the family resisted the pressure to join the unified agricultural cooperative (collective farm), which was established in Velká Losenice in 1952. They finally joined the cooperative in 1956. In 1955, Berta graduated from elementary school with honors. She wanted to study and to be a teacher, however, as the daughter of a “kulak”, she was not allowed to study and for political reasons, she was not even accepted to an agricultural high school. In 1960, she married Josef Fišar, the son of a farmer from the neighborhood. Until her retirement, she worked in a collective farm in a cowshed. When her son was studying at the university in Olomouc, she was afraid that he would be expelled from the university for political reasons and that he would have a similar fate as the witness herself. After the Velvet Revolution and regime change, the family was restituted, but after her husband’s death, Berta no longer dared to start farming alone.