“I didn’t know who I was, where I was, or what happened to me.”

Download image

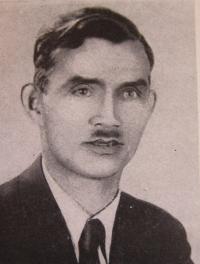

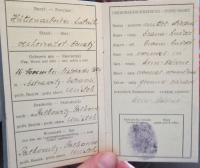

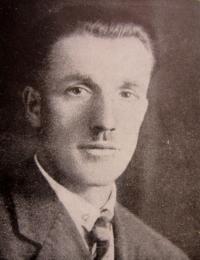

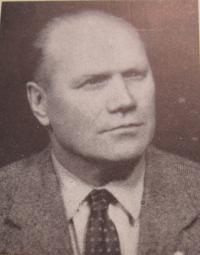

Jarmila Foralová, née Kišová, was born on April 27th, 1927 in Palkovice in the Beskydy Mountains to the family of a metal worker. Her parents and most of her relatives believed in a classless, just society as they were members of the Communist party. When the Nazi occupation began, the family immediately joined the Resistance, and her father, František Kiša, was executed in the Mauthausen Concentration Camp on the 5th of November, 1941. The witness claims that altogether eleven of her relatives were arrested during the war, eight of which never returned home. Jarmila Foralová herself as a fifteen-year-old girl became an important messenger for the partisan group Jiskra (Spark), led by her uncle, Jakub Bílek. She barely avoided capture several times. Even so, she ended up in a Gestapo interrogation room in November 1944. As she did not want to betray anyone, she was subjected to brutal torture, finally falling unconscious and for the following week, she did not know her own name or where she was. But the Gestapo had no idea that they had arrested a messenger for the partisans, and so in the end, they sent her to hospital. After recovering, she continued with her resistance activities. When the war was over, Jarmila Foralová became an official member of the Communist party. She remained faithful to the Communist party for her whole life and fully agreed with its ideology. Despite this, she claims that she was always a supporter of parliamentary democracy. She also says she did not agree with the death penalties carried out during the 1950s or with the relaxed politics of 1968.