I wanted to get a hold of my life

Download image

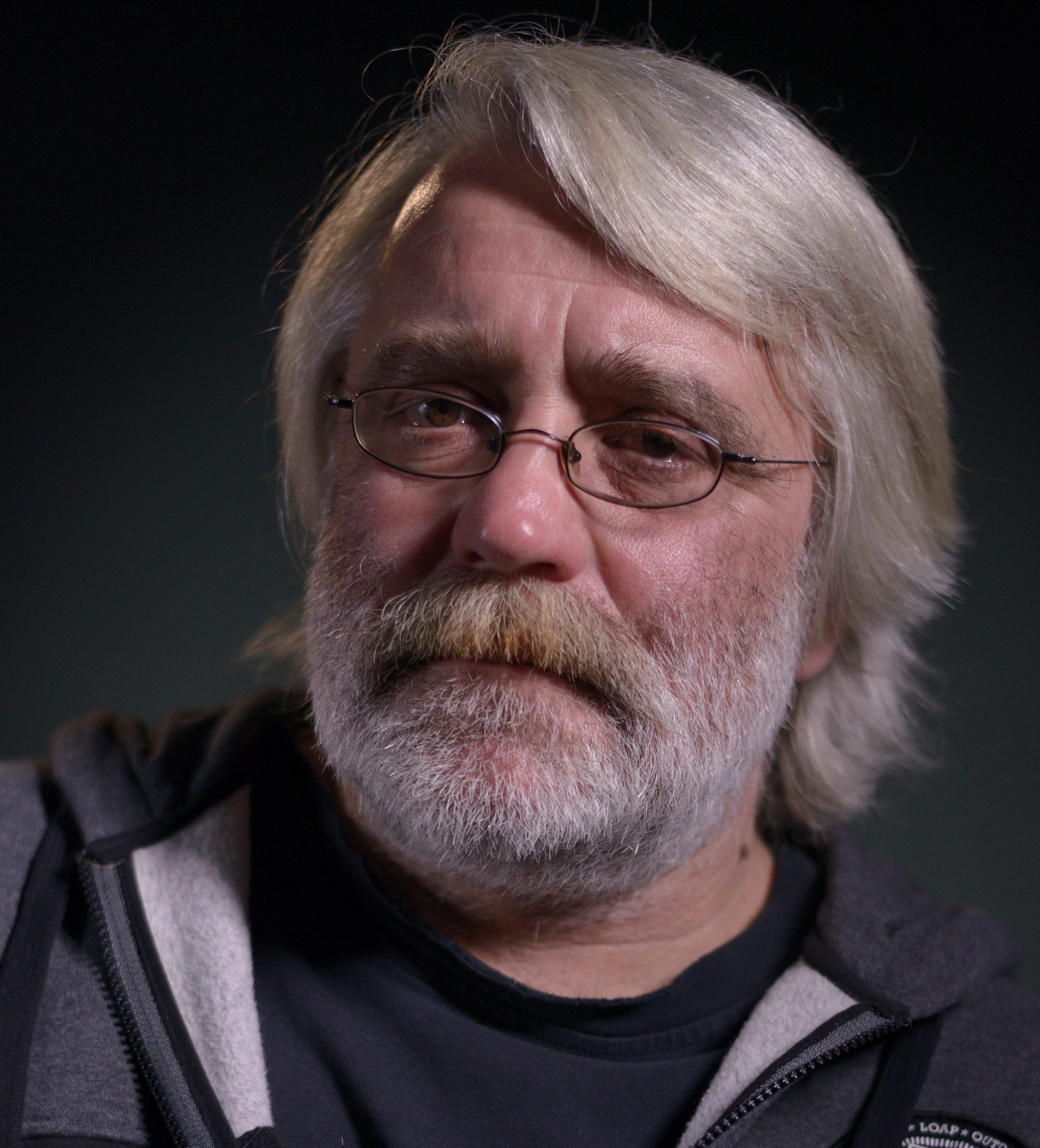

Jaroslav Formánek was born on 27 April 1960 in Veselí nad Moravou. His father worked as head of a staff canteen and his mother as an accountant. The family lived with Jaroslav’s grandparents in Veselí in a house located near the river Morava. This is where Jaroslav was woken up in the morning of 21 August 1968 by occupants’ tanks and soldiers. In 1979 he graduated from a grammar school in Strážnice where he and his colleagues performed several theater plays based on his scripts and where he published his first pieces in a student newspaper. He enrolled at the Faculty of Pedagogy in Brno but left the studies shortly thereafter. He worked in ironworks in Veselí before moving to Prague where he found a job as a driver in film laboratories at Barrandov. He was in contact with members of the underground including the band Plastic People of the Universe, they would meet among other places in restaurant U Šolců. He had to undertake military service in Cheb which was the last straw to his decision to leave the country. In 1982 he worked in an agricultural collective in Chýně, later him and Rudolf Kučera established another collective in Kamenné Žehrovice and worked in apartment repairs in Prague’s Lesser Town. Through Rudolf Kučera who published an illegal magazine Central Europe, Jaroslav Formánek had access to the so-called samizdat literature and magazines. He attended seminars held in apartments, read a lot and gradually got into writing. His first short story was officially published in 1988 in Mladá Fronta, one of the leading Czech dailies. He was continuously denied the necessary approval to travel abroad. On 15 April 1989 he immigrated to France where he got an asylum at the beginning of July. In Paris he was in contact with the Czech community formed around Pavel Tigrid. The poet Jiří Kolář helped him overcome initial difficulties. In 1992 he was awarded French citizenship. In 2007 he returned to the Czech Republic. He wrote several books, currently works as a journalist, a radio publicist and a translator.