I only learnt about our family history while in Israel

Download image

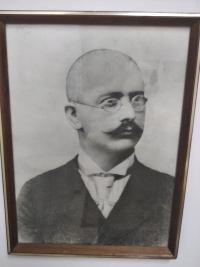

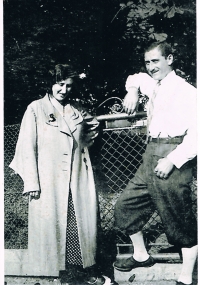

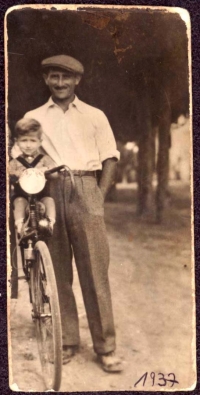

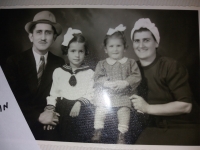

Pavel Friedmann was born on March 25, 1948 in Michalovce in eastern Slovakia into a Jewish family. He spent his childhood in the village Malčice. His parents, father Izák and mother Dora, have survived the holocaust - his father in the concentration camp Dachau and his mother was hiding in Hungary with falsified documents. Pavel’s father worked as a pharmacist in Malčice and his mother was helping him. After completing elementary school in Malčice, Pavel continued with his studies at the secondary technical school in Košice. In 1964 the Friedmann family decided to relocate to Israel where his mother’s four siblings had already been living since the pre-war times. Pavel did his three year military service in Israel in 1967-1970, then he graduated from secondary school and in 1975 he completed his studies at the faculty of electrical engineering. In 1981-1983 he subsequently continued studying at the University in Buffalo in New York State. From 1985 he has been working for an electric power plant in Israel. In 1994-1995 he served as a representative of the Jewish Agency in Prague. With his wife Relly they raised a son and a daughter. Pavel Friedmann lives in Haifa.