As a kid, I couldn’t understand why he confessed

Download image

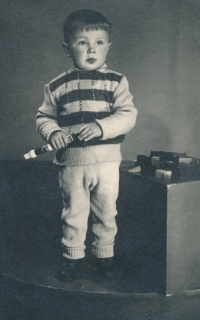

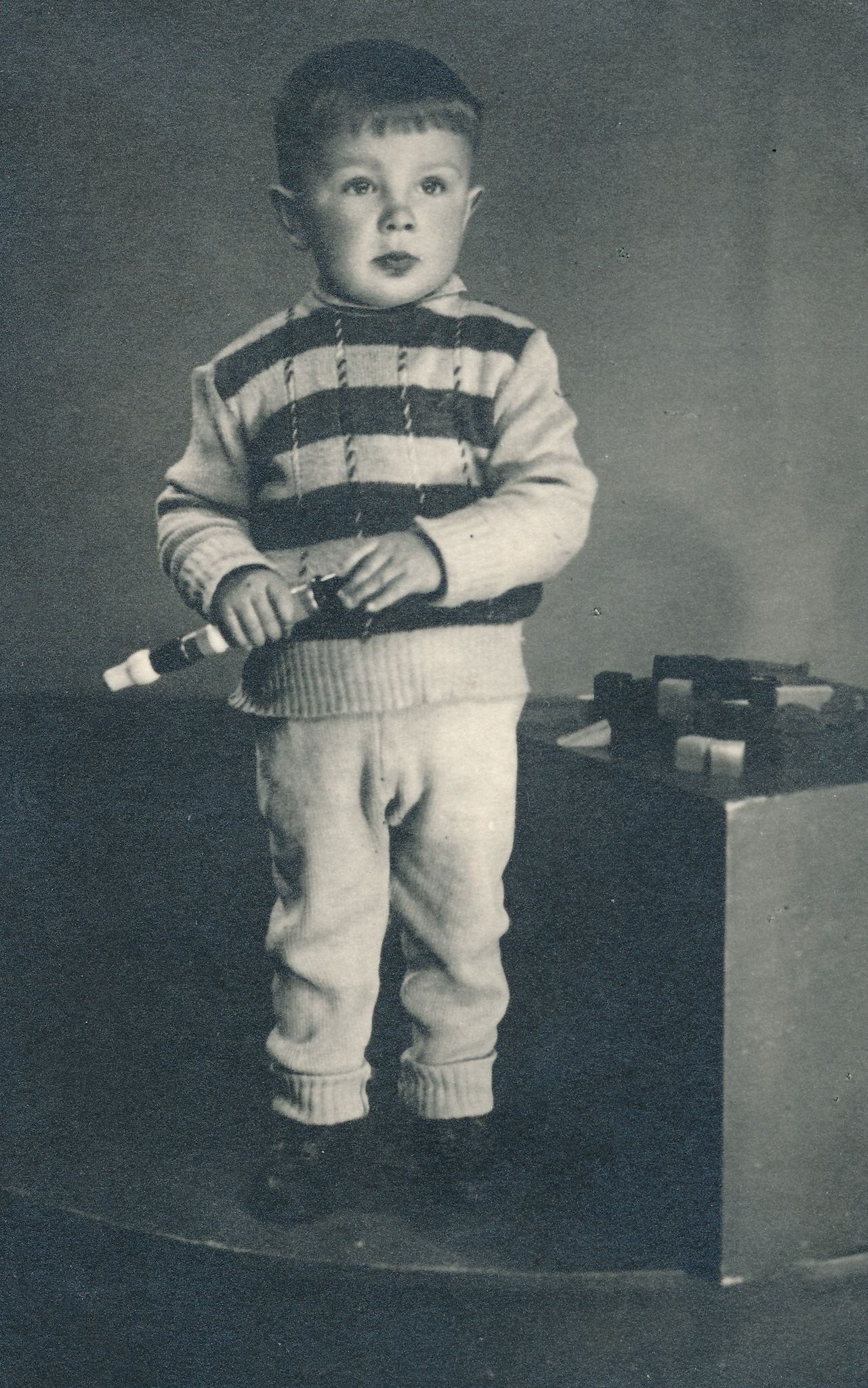

Vladimír Fulín was born on 27 June 1947 in Prešov into a family of teachers, Marie and Vladimír Fulíns. His uncle Bohumil Fulín (1912-1993) was a member of the Jan Žižka Partisan Brigade during the war. For his participation in the anti-Nazi resistance he was awarded the war cross and the medal for valour. In 1950, uncle Bohumil sheltered three anti-communist resistance fighters from the group Hory Hostýnské. He was arrested one year later and sentenced in 1952 to 11 years in prison for high treason. He served his sentence in a camp at the uranium mines in the Jáchymov region, and was released only thanks to an amnesty - probably in 1960. After graduating from the high school in Sabinov, Vladimír Fulín entered the branch faculty of technology of the Brno University of Technology (VUT) in Zlín, then Gottwaldov, in 1966. As a student, he witnessed the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops, after which he took part in student protests. Subsequently, he had to leave the school, but managed to finish it part-time. He worked in a plastics processing factory in Vrbno pod Pradědem and then, until the Velvet Revolution, in the same industry in Nitra. Vladimír Fulín lived in Prague in 2024.