Either we’ll get arrested, shot, or we’ll have a new life.

Download image

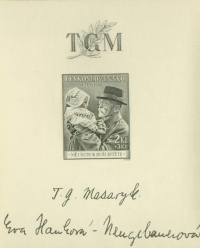

Eva Haňková, née Neugebauerová, was born on 20 May 1925 in Prague. From the age of two she lived in Žďár in Moravia (today Žďár nad Sázavou) with her parents Antonie and Richard Neugebauer, who owned and ran a steam sawmill in the village. In 1928, a famous photograph was taken of President Masaryk holding the three-year-old Eva, dressed in her Kyjov costume, in his arms. The photograph was later used as the basis for a postage stamp. Eva Haňková graduated from grammar school in Pardubice in 1944, then studied languages at the Institute of Modern Languages in Prague. She married Ladislav Haňka, an agricultural engineer, and in 1950 she fled with him to Bavaria via Šumava. The following year they managed to emigrate to the United States. They found their first refuge in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, then moved to Kalamazoo, Michigan. Eva Haňková taught languages at a high school there. They raised two children. In 2000, Ladislav Haňka founded a foundation named after his wife at the grammar school in Žďár nad Sázavou. Every year the best graduate of the grammar school receives a scholarship and a commemorative silver coin from the foundation. In 2022, Eva Haňková was living in Kalamazoo.