I didn’t expect at all, I could be accused for spying

Download image

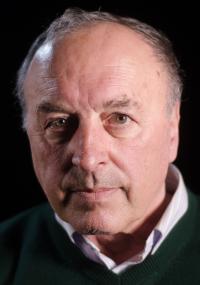

Petr Hauptman was born on August 7, 1946. His father was detained in the 50’s as an alleged secret foreign agent. He was sentenced to 14 years, which he spent in Communist prisons and labor camps. Hauptman studied architecture. In the 70’s he started to work at the State institute for reconstruction of historic towns and buildings. There he was under pressure to become a member of the Communist party, so he decided to quit. Then he found a job at the customs office. In the 70’s, his wife mentally collapsed because Communist officials bossed her around at work. In the beginning of the 80’s, Hauptman had to fill in for an ill collegue in the customs office on the western boarders. He decided to take advantage of the opportunity to emigrate. During a process of approval of a new bridge over a border brook, he escaped to Bavaria in Germany in October 1982. There he acquired political asylum and developed a plan to move the whole family to Germany. But the situation completely changed after his son became seriously ill with encephalomyelitis. Despite Hauptman suppositions, he was arrested upon his return home, sentenced for a few years, and crossed the borders back to Czechoslovakia in December 1982. He was interrogated and accused not only for illegal crossing of the state borders but also quite unexpectedly for spying according to the clause § 105. On September 12, 1983, he was finally arrested and sentenced for 10 years in prison. For the whole sentence, he served in the Minkovice Prison where he had worked as a glass cutter. His wife and children were supported by VONS fellowship and by many people from abroad during his detention. Hauptman was released on January 16, 1990 upon personal pardon granted by President Vaclav Havel. Soon he started to work at a technical commission of OF (Civic Forum). As early as February, he traveled abroad to collect gifts for OF. He worked with copying machines for next 11 years until he prematurely retired.