She grew up next to uranium mines. For her classmates she was always just a German rat

Download image

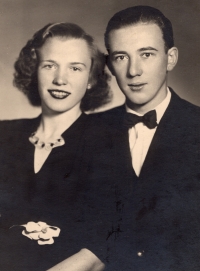

Sonja Hefele, née Christl, was born on 5 February 1949 into a German family. Her father, Erich Christl, came from Loket near Sokolov, her mother, Ilse Sterlich, from Opole in Silesia. They met in a hospital near Berlin. The Christls were not deported probably because Erich’s father Alfred worked in a power plant near Sokolov. Sonja grew up successively in Loket, Nové Sedlo and Horní Slavkov near the labour camps. Erich worked as an explosives handler in the uranium mines there. The family repeatedly applied for permission to emigrate to Germany, but they weren´t granted it until 1964. The family left Czechoslovakia in November after they had to pay the school fees for Sonja´s education. They settled in Augsburg. Fifteen-year-old Sonja Hefele used to cry because of the change of ambience, even though she had been a frequent target of bullying as a German in the Czech primary school. In 1970 she married Wolfgang Hefele. Two years later, she returned to her native country with her husband for the first time. In 1985, she made a ten-day motorcycle trip in Czechoslovakia. She worked as an interpreter, translator and journalist at a local radio station. After 1989 she promoted German-Czech relations and cultural cooperation between the two countries. She also met Václav Havel. In 2021 she initiated a partnership between Augsburg and Liberec. In 2021 she was awarded the Liberec City Medal. In 2022 she was living in Augsburg.