My father told me that this is the first and last time we see each other

Download image

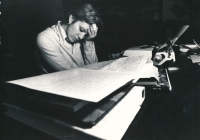

Eva Hejdová was born on 26 August 1953 in Prague. She grew up as an only child with her mother and her parents, her father showed no interest in her. She had relatives in Vienna, who visited her every year, and even as a child she perceived the abysmal difference between life in communist Czechoslovakia and life in the West. In Vienna, she was also caught up in the news of the occupation of the country by Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968. Even then they considered emigrating, but eventually returned. Her father emigrated to the United States in 1969, which negatively affected her cadre profile. While still in high school, she worked as a freelance photographer with the daily Mladá Fronta, which facilitated her admission to the Faculty of Journalism at Charles University in 1972. While studying, she married and had a daughter, Kristýna, but soon divorced. For some time she worked shooting commercials, as a book editor, and was a freelance photographer. Later, she was employed by the magazine Československý architekt (Czechoslovak Architect) and thanks to this she was able to travel on business to the Biennale in Venice, Italy. Already in Italy she considered emigrating, but it was not until 1985 that she left for the USA. She settled in New York, working for the Atlas photo studio and private clients (e.g. the American Craft Museum, the Smithsonian Institution, the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Heller Gallery). She married for the second time, acquired American citizenship and had a son, Tomas. However, she was unable to bring her daughter Kristýna to the United States until the Revolution. She lived in New York until 2005, when she returned to the Czech Republic. In 2024, she was photographing for private clients in the USA and the Czech Republic and living in Rožmital pod Třemšín.