As if you switch a switch. Democracy was suddenly over…

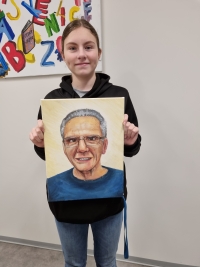

Download image

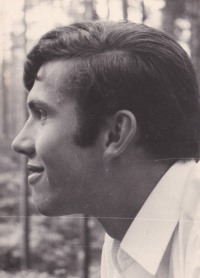

Otakar Hlavín was born on 12 March 1949 in Prague. Both parents worked in a printing office, his father worked as head of the manual typesetting shop, mother in the printing office of “the People’s Democracy” on Wenceslas Square. Otakar Hlavín attended elementary school in Resslova Street in Prague, from 1964 he studied at the Secondary School of Mechanical Engineering in Karlín, and he graduated from it in 1968. He did his military service in Kbely from 1969 to 1971. He got married in the mid-1970s and they had a daughter. He remembers his childhood in the 1950s and how children were formed from childhood to obey the communist regime. He talks about the time of loosening in the 1960s and how he experienced occupation as a nineteen-year-old young man. They lived by the Jirásek bridge which was occupied by the Soviet tanks whose barrels were aiming at their windows. During normalization, he resisted pressure to join the Party even though he would have gained numerous benefits from membership in the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. For instance, a possibility to gain a flat that his young family needed. They solved their urgent housing situation by buying a dilapidated house in Líbeznice, which they then reconstructed for ten years. Otakar describes the reality of a young family in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1989 he joined Civic Forum in the company and in the village of Líbeznice, where he was elected mayor after the revolution in 1989. He served as mayor for the next twenty years.