Instead of receiving an award for saving the passengers, the father was investigated. He was accused of conspiracy

Download image

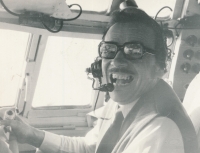

Ilona Horáčková was born on 24 May 1955 in Brno. Her mother was Eva Horáčková, née Procházková. Her father Břetislav Horáček worked as a military pilot after the Second World War, but in 1961 he left the army and started flying transport planes for ČSA (Czechoslovak Airlines). As a captain, he piloted CSA flight OK 096 on 8 June 1970, one of the first widely known cases of emigration by hijacking on a domestic flight. By his prompt action and reassurance, he rescued the passengers on the hijacked Ilyushin IL-14 and landed safely in Nuremberg. Upon his return to Prague, he was accused by State Security of conspiring with the hijackers and demoted to office work. Although he subsequently won a court case for his dismissal, he never returned to transport flights as a captain. Ilona Horáčková became an eyewitness to the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops on 21 August 1968 on Wenceslas Square in Prague. During the normalisation, she participated in several banned rock music concerts. After the Velvet Revolution in 1989, she and her husband set up a security agency, with which they also guarded dangerous places in the wild 1990s, such as the infamous U Holubů restaurant, where the Russian-language mafia used to meet. At the time of the interview in 2023, she was living in Prague.