Let´s try cultivating our environment and mutual relations

Download image

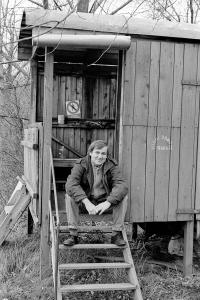

Petr Hořejš was born on 7th September, 1938 as a fourth child in a Czech family living in the first republic Bratislava. His father taught music science at a university and was active in several magazines. Worsening relations between Czechs and Slovaks before the second world war climaxed by a bomb explosion in the father´s office. The family moved fast to Prague shortly after the signing of the Munich Agreement. Compared with many other families with a similar fate their friends managed to get a flat in Čelakovské sady. The witness suffered by panic fear of the sound of sirens warning against air-raids and was scared of staying in a terrifying cover cellar. Therefore he was moved together with his aunt to a rented villa in Stříbrná Skalice, where in 1944 he started in a local two classrooms school and experienced celebrations of the end of war and our liberation. After that he began studying at the basic school at the Piece square. The whole family got excited to build socialism. Petr Hořejš joined the pioneer movement and soon became its head. His excitement sobered up after political processes took place in 1950s. He began studying eleven-grade school and after graduation he mastered a study of journalism at the Philosophical faculty of the Charles University. With his school mates, Ladislav Jiránek, Přemek Podlaha, Jiří Hanák, Karel Tejkal and others they didn’t hide their disgust over current politics in the state and journalism too. In 1962 he left his reporter´s job in a Czechoslovakian radio and began working for the Albatros publishing. After occupation of the republic in 1968 he got engaged in non-violent resistance against republic occupation. In 1970 during political reviews Petr Hořejš was fired from his job. He could not find any suitable job and could only feed his family by publishing under a pseudonym Petr Hora in the Mladý svět magazine. In 1980s he worked as a pumper for Vodní zdroje Praha. He soon got used to living in a van, which he parked in front of a chemical factory in Kralupy. At the time he began working on a cycle called the Rambles through the Czech Past. Its publishing was a huge readers´ success in Mladý svět. In 1990 he became a director of the Albatros publishing. Petr Hořejš was active in the Holiday School Lipnice, co-founded Lipnice scholarship fund and the Pangea foundation. He died on July 27th, 2023.