An oppressor knows only to oppress

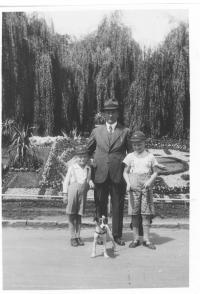

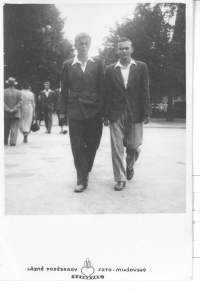

Vladimír Hradec was born on the 30th of May 1931 in Poděbrady. In 1942 he became acquainted with the Mašín brothers who had moved into the town at that time. He would meet Ctirad on the way to school, but no close friendship was initiated. They did not become close until after the war. After graduating, Vladimír started studying chemistry while at the same time helping the Mašín brothers with their activities, though he was not privy to their plans. After the Mašíns’ escape, the whole of the Hradec family (Vladimír, his brother, father and mother) were arrested and all of them were given harsh sentences (Vladimír Hradec was sentenced to 22 years). He was an inmate of the prisons and labour camps in Leopoldov, Jáchymov and Bory. After his release in 1964 he worked at Spolana Neratovice [a chemical plant - transl.].