They could return to their own house but first, they had to buy it back from the state

Download image

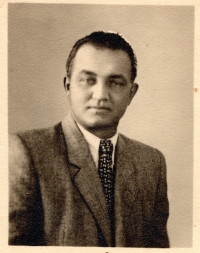

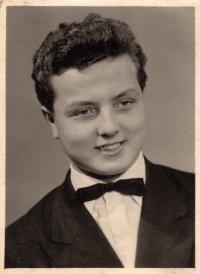

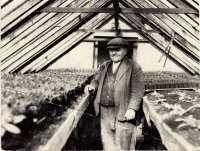

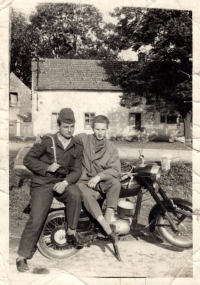

Josef Hrdý was born on the 19th of October in 1944 in Pardubice to an old family of estate holders who lived in Horní Ředice near Pardubice. After the Communist coup in February 1948, hard times fell on the family. The father was declared a kulak and enemy of the state, as such, he had to meet higher produce quota and he got lower prices for the produce he delivered. During the 1950’s, the estate was searched many times, during one search, the officers confiscated a family chronicle that charted the family history back to the end of the 17th century. Josef Hrdý senior refused to join the Unified Agricultural Cooperative which was established in 1955 and in the same year, he was sentenced to ten months in prison, loss of civic rights and confiscation of all his property. A part of the punishment was banishment to at least 20 kilometres away from the previous place of residence. From HR, the family thus moved to Šnakov in Vysoké Mýto. After some time, they moved once more, to Blížňovice near Chrudim. Josef Hrdý junior could not pursue any higher education so he started working in the repair shop of a state farm. After some persistence, he was allowed to go to a trade school to apprentice for a smith and farrier. He graduated from the school as best in class but he was not allowed to study further. Only after having finished his compulsory army service, he was able to take distance courses and graduated from the secondary technical school in Chrudim. In 1968, the family was allowed to return to the estate in Horní Ředice, however they had to buy back a house that was a part of it. In 1970, Josef Hrdý got married, they had two children together with his first wife. Apart from his day job, in his glass house and in his garden, he grew vegetables for sale. During the Velvet revolution, he was the head of the strike committee in the Moravany branch of the Czechoslovak Automobile Repairs. After the company was unsuccessfully privatised and fell apart, he started an agricultural business. He grew and sold cattle, which he kept doing until he was diagnosed with a grave illness in 1995. In present, Josef Hrdý lives on his estate in Horní Ředice.