The theatre in the outskirts was freer

Download image

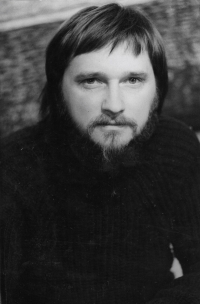

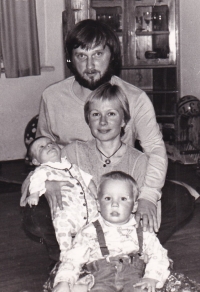

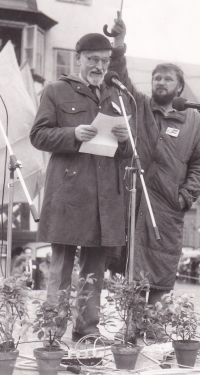

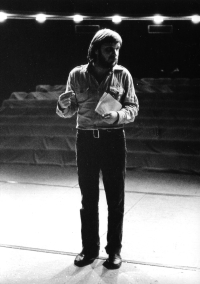

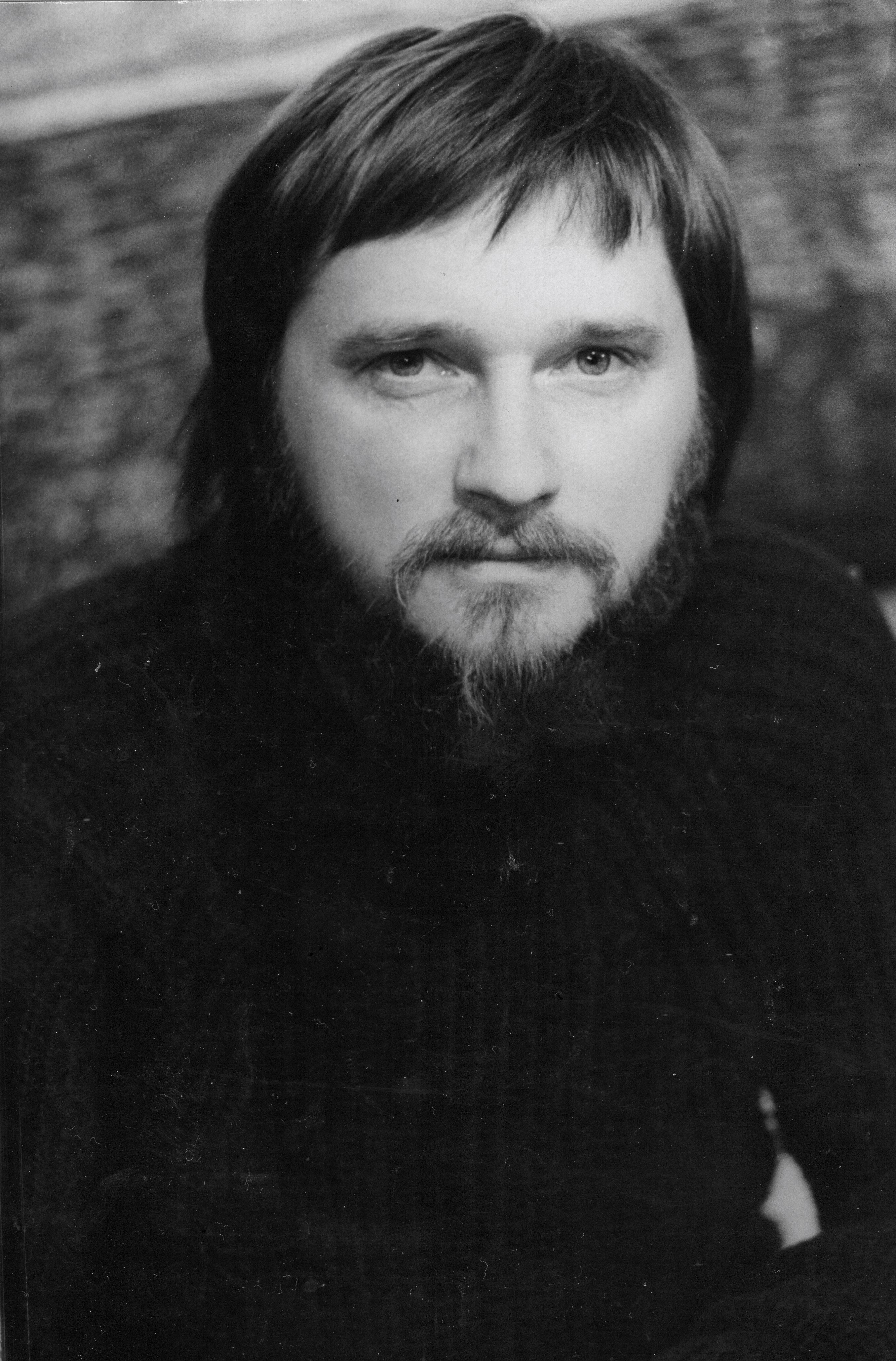

František Hromada was born on 6 December 1941 and as a young boy at the end of the Second World War he witnessed the Allied bombing of Prague. In September 1945, he moved with his family to Mariánské Lázně, where his grandfather ran the Excelsior guesthouse. In the early 1950s, his father spent almost three years in prison for printing a copy of Dikobraz with a caricature of Gottwald. In the army in Židenice, František Hromada experienced military manoeuvres during the Caribbean crisis in 1962. He graduated from the JAMU in Brno, but during his engagement at the operetta in Pilsen he refused to sign the Anticharter and had to leave the theatre. He had engagements in Hradec Králové and Šumperk and in the 1980s he joined the theatre in Cheb as a director. In the mid-1980s, he became a candidate for the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia to give the theatre patronage and enable it to create non-conformist productions. In November 1989, he co-founded the Civic Forum in Cheb. After 1989, he served as director of the West Bohemian Theatre from 1991 to 1999. In 2022 he lived in Martinov near Mariánské Lázně.