I still think it was a German officer who had me released from the labour camp

Download image

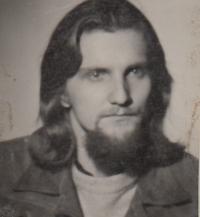

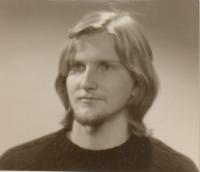

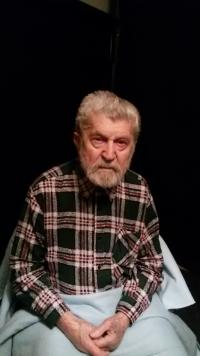

Jaroslav Hrubeš was born on 13 October 1926 in Pečky, into the working-class family of Jaroslav Hrubeš and Františka Hrubešová, née Plačková. He had three sisters. When his father’s wagon service failed, the family was harshly hit by unemployment during the economic crisis in the 1930s. Struggling to sustain a family with four children, his father - like others of the poverty-stricken inhabitants of Pečky - stole coal from parked cargo wagons, which he then sold or exchanged for other goods. Jaroslav trained as a mechanic and worked in Vysočany during the war. In 1944 he was to be transported to Terezín for refusing to work twelve-hour shifts when still a minor. His sister bribed the officials with 40,000 crowns, and so Jaroslav was “only” sent to the labour camp in Kamenný Přívoz. He worked in the nearby quarry. He was released two and a half months later, apparently on the intercession of a German officer. After his return he survived the air raids on Prague-Vinohrady. His son, who was not able to fulfil his ambitions in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, emigrated from the country in the 1970s, but died prematurely in Germany in 1990.