On the 17th of November five of my clients were still sitting in prison

Download image

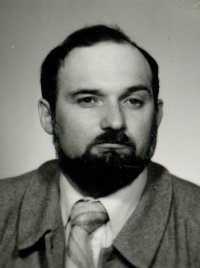

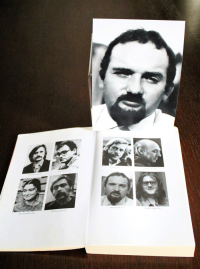

Milan Hulík was born on 22 March 1946 in Kolín to the family of the owner of company involved in the mining of sand. After the communist coup in February 1948, his father lost the company, and in the second half of the 1950s he came to find out that the communists ruling the country had been only renting out his machines. At court he succeeded in getting the Czechoslovak Republic to reimburse him for the lost rents. Retaliation from the totalitarian regime was swift, and the former businessman Hulík was taken to court in 1958 and sentenced to 12 years for the falsified elicitation of tax breaks and for anti-communist activity. Visits to see his father in prison traumatized Milan Hulík. The courts ended his sentence, under conditions, in 1967. Milan Hulík was an outstanding student in his basic schooling, but communist power, considering him the son of a class-enemy, only made it possible for him to apprentice as a mason. After some time, however, he was able to go to Prague and attend a vocational program specialized in construction in Prague, where he finished his secondary education successfully. Then he undertook his two-year military service, which he was able to leave early thanks to him faking having psychological issues. He took the entrance exams for the Faculty of Law at Charles University, from where he graduated in 1974. At the start of his career, he worked in entrepreneurial law and in 1976 he became an attorney’s clerk in Prague. In the second half of the 1970s and 1980s he defended a number of dissidents – for example František Stárek, Petr Cibulka, Petr Uhl, and Jarmila Bělíková. After 1989, he started working as the director of inspection division at the Office for the Protection of the Constitution and Democracy (today the Security Information Service). Additionally, he served as the chairman of the vetting commission of the Board of Corrections (today the Prison Service), where he later on became the first deputy of the general director and where he attained the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1995, he returned to the legal profession and he was able to study history at Charles University and acquired his doctoral degree. In 2020, the witness was living in Prague.