Nearly everyone of us students at the faculty of theology has been contacted by the StB

Download image

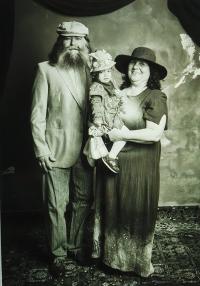

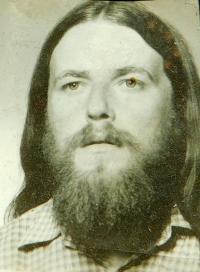

Václav Hurt was born on May 11, 1957 in Čáslav, but he spent his childhood in the mountain hamlet Hořejší Herlíkovice in the Krkonoše Mountains where his parents worked as administrators of a leisure resort ran by the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren. In 1976-1981 he studied at the Komenský Evangelical Faculty of Theology. During his studies he married Ursula Weissová and they gradually had four children. After his first placement as a pastor in Merklín he tried to organize various meetings and thus to foster a sense of community among young evangelical believers. As a consequence, he was being regularly summoned to interrogations by the StB and eventually in 1985 the authorities annulled his permission to serve as a pastor. For several months he then worked as worker in a bakery and in a brickworks before he was sent to the other end of the country, to Hrabová, where he was able to serve the believers again. However, he was not deterred by the pressure and he continued meeting people who were actively struggling against the communist regime. Václav was among the participants of the protest rally in Národní Street in Prague which took place on November 17, 1989 and which marked the fall of the communist regime. Together with other people he then established the Civic Forum in Hrabová and he served as an evangelical pastor there until 1999. Subsequently he served in Bošín, then again in Mladá Boleslav and from 2012 he serves in Litomyšl. As an army chaplain he also took part in the SFOR II mission in Bosnia at the turn of the millennium and for several years he and his wife have been devoting their time to foster care for abandoned babies in order to prevent them from developing problems stemming from their stay in an institutional care facility.