To do good

Download image

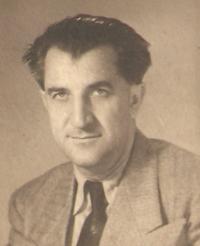

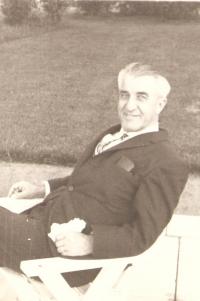

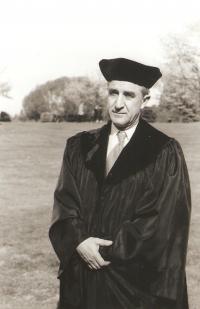

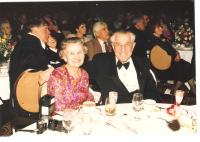

Milena Janda was born as Milena Krajinová on 7th April 1935 in Prague. The family had its roots in Moravia. father Vladimír in Třebíč and its surroundings and mother Marie in Tasov. Both came from families of teachers who believed in the Masaryk values of the First Republic. After the Munich Treaty, the life of five-year-old Milena changed dramatically. Father, Professor of Botany at Charles University, became a leading figure in the resistance movement in Czechoslovakia, mother was sent to a concentration camp and later the father had to go into hiding. Milena lived with her relatives in Moravia and could see her parents only a few times during the Nazi occupation. After the war, her father became the General Secretary of the National Socialist Party and immediately after the February coup had to emigrate. In the summer, the rest of the family crossed the border via London to Vancouver. There, Milena studied and devoted her professional life to opera. She translated opera subtitles not only for the Vancouver UBC Opera but also for the Prague National Theatre. She made her first visit to Czechoslovakia in 1969. She came again, this time with her parents, in 1990 when Prof. Krajina received the highest state award from President Václav Havel, the Order of the White Lion.