They were arrested by partisans after the war, even after his father survived concentration camps and a death march

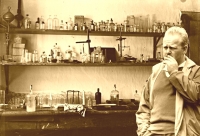

Download image

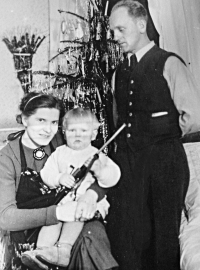

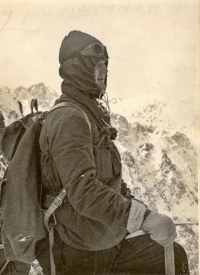

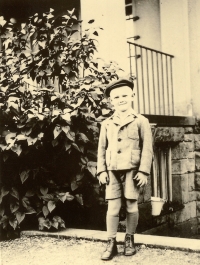

Miroslav Jech was born on 1 February 1938 in Háje nad Jizerou in the Semily region. As a two-year-old he witnessed his father being arrested by Gestapo servicemen from Jičín. His father, Adolf Jech, was taken away by the Gestapo men who left little Miroslav standing in the middle of the road. Eventually, local villagers took care of him. His father had been arrested due to his alleged involvement in building forest hideouts where young men who wanted to avoid being drafted in the Wehrmacht were supposed to be hiding. Nazis sent his father to prison, then he spent five years in concentrations camps and survived a death march. He passed away soon after the war at 46 due to pulmonary condition. In the house provided by the factory – where the Jech family had been living – there was a family of German refugees from Northern Poland staying at the end of the war. Miroslav Jech witnessed brutal abuse of this farmer family by local young men, partisans from a neighboring village. After Miroslav’s father returned from a concentration camp, they had to face more hardships. They were arrested by people from a neighboring village posing as partisans. They were released only after the witness’ father had been identified by an old friend of his. After the war, Mirolsav Jech befriended their ‘half-German’ neighbors who weren’t expelled from the country. Their families were allowed to stay in Czechoslovakia after the war because their fathers, as electricians, lathe operators or railwaymen, were essential for the border area. He taught his friends Czech, as he knew some German from the Protectorate era. He graduated from school of chemistry and technology and had been working all his life as a textile dyer in Raspenava. In his spare time, he had been doing athletics, he was an alpinist and a tourist. For thirty years he was a mountain rescue service volunteer in Smědava in the Jizera Mountains and rescued tens of tourists who got lost or wounded. On 23 April 1992, he was a part of a rescue team looking for two French humanitarian aid planes that crashed at Smědavská Mountain. Four people died in the crash. In 1960, Miroslav Jech took interest in amateur meteorology, he had been monitoring participation, temperature, humidity and wind speed, as well as air quality. He had been sharing all the data with meteorologists in the city of Ústí na Labem. In Hejnice, he was able to detect even a unique phenomena, the so-called warm Alpine gust. After retiring, as for 2021, he had been living in Hejnice.