“I knew I had to do something to serve others.”

Download image

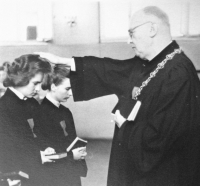

Marta Jurková was born July 1st 1940 in Prague as the second child of František Přeučil and Růžena Přeučilová, b. Knoblochová. Her mother was a seamstress and her father was a tailor, however neither one of them really worked in these respective professions. Both parents were ardent members of the Sokol movement and patriots who honored the ideals of Masaryk. In the early 1930’s, Marta’s father was promoted to the position of editor and secretary of the Czechoslovak Tradesmen’s Middle-Class Party in Pardubice. Marta’s brother, Jan, now a well-known actor, was born there in 1937, and in 1940 the family moved back to Prague, where father continued to work as an editor and publisher. During the occupation, František Přeučil also took part in resistance activities, for which he was later decorated after the war. In 1945, František Přeučil joined the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party, served in its central committee, and even became a member of the interim national assembly for this party. A year later, he was elected to be a deputy to the Constitutional National Assembly. After the war ended, he also became the founder and leader of the publishing house known as Pamír. His activities in the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party after February, 1948 did not go unnoticed by the State Police, and in the early morning of November 8, 1949, he was arrested and taken to a detention facility. In the following trial, with Milada Horáková and many others, František Přeučil was sentenced to life imprisonment. František Přeučil’s imprisonment naturally had grave consequences upon the entire family. They were forced to move out of their apartment, struggled financially, and faced persecution. Marta and her brother were not permitted to study. In spite of this, Marta’s mother managed to get her registered at a technical trade school. Only two weeks later, however, she was found and sent home. Luckily, she managed to take a one-year typewriting and shorthand course and found a job at the Armabeton Cooling Systems company. After the family was forced move to the Braník neighbourhood in Prague, little Marta followed her mother’s wish and began attending religious classes with the Czechoslovak church pastor, Václav Mikulecký. This pastor ended up having a significant formative influence on young Marta, who later decided to join a youth group in the Braník parish of the Czechoslovak Hussite Church. Pastor Mikulecký was the leader of this youth group until he was eventually forced transfer to another parish. Young Marta’s faith was not very strong at first, however. She liked the activities of the youth group and enjoyed going to the various camps, which the group members basically organized themselves after pastor Mikulecký’s leave, but it took her some time to fully embrace the decision to believe. The crucial point that influenced her adoption of faith was the moment when she was to lead the devotion for the other youth group memebrs for the first time. She opened the Bible at random and found these words: ´Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed.´ After this event, as Marta’s commitment to faith grew, pastor Mikulecký stepped back into her life and suggested she study theology. He managed to get approval from a state official that permitted her to study, solely because it was for matters of the church. He also convinced her mother, who originally found it unthinkable, that Marta should study at a theological faculty. In 1956, Marta took preparatory courses before entering the Hus’s Czechoslovak Theological Faculty in Prague. During her studies, she also became an academic assistant to professor Trtík for systematic theology. Eventually, though, love trumped theology. After her graduation in 1961, Marta married her classmate, Stanislav Jurek, with whom she had three children in a short time and then a fourth later on. In 1959, her mother died from mourning her husband’s imprisonment. Four years after, however, he was released from the communist prison after fourteen years of imprisonment. After Marta Jurková assumed her new role and title as pastor, her first assignment was set to be the parish of Czechoslovak Hussite Church in Prague-Zderaz. Yet due to her family background, the only place where she was permitted to work as a pastor was Litvínov, in northern Bohemia. She served in Litvínov until 1968 when she and her family moved to be with her husband in Říčany, where she was able to work in the Prague-Braník and Prague-Podolí parishes or about a year. Then, between the years 1969 and 1978, the parish in Říčany became her established home parish. Throughout the 1960’s and 1970’s, she and her husband were also active in unofficial structures within the CzSHC, whose members were organized around the leader, pastor Václav Mikulecký. Because of her father’s prior experiences, pastor Jurková was “spared” problems with the State Police. Her husband, on the other hand, did have to face conflicts with the state system. In the 1970’s he even left his position as pastor due to numerous disagreements with the state institutions presiding over the church. Subsequently, in 1978, his and Marta’s marriage broke, and Marta promptly left her pastoral service, as well. For thirteen years to follow she worked as a nurse, continuing until she founded Horizont in 1989, a church institution providing care for senior citizens. She is still serves in the Horizont´s board. In 1990, she also returned to the ministry of the Czechoslovak Hussite church, first as a member of clergy and then as a pastor in the Prague-Dejvice parish, where she has been working until now. She also began a club in the post-1989 years, the Club of Dr. Milada Horáková, which centers around continuing the work of her father.