I never forgot the burial of capitalism

Download image

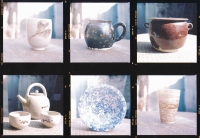

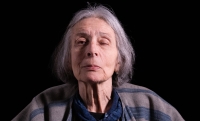

Eva Jůzová, née Řehová, was born on the 8th of November in 1943 in Prague; she lived with her parents and her siblings Marie and Karel Řeha in Kralupy nad Vltavou. Her father was a watchmaker, his mother helped him around the shop, they were both practicing Protestants. After the end of WWII, they moved to Kroměříž where her father took over the shop of his master clockmaker Antonín Minář. In 1952, the Communists seized Karel Řeha‘s workshop and for the rest of his life, he worked as a repairman of fine machinery in a factory in Chropyně. Eva was talented in arts but as a daughter of a former business owner and a practicing Protestant, she couldn’t go neither to a high school nor pursue any further studies. She had excellent grades so after some pleading, she was allowed to enrol to a high school and in 1961, she got to the Faculty of Arts of the Jan Evangelista Purkyně University in Brno [Note: Nowadays, it’s the Masaryk University; university in Ústí nad Labem now bears the name of Jan Evangelista Purkyně] to study art history. She graduated in 1966. She got a job in the National Heritage Institute in Plzeň, a year later, she got a job at the department of art history at the Arts Faculty where she was preparing for her doctoral exams under the supervision of [the philosopher] Jan Patočka. When she was still a student, she published articles in the magazines Host do domu [Guest to the House, a renowned literary magazine] and Věda a Život [Life and Sciences] where she remained until its demise in early 11970’s. In the autumn of 1968, she was for a study stay in Vienna and her friends tried to persuade her to emigrate. She did not want to leave her aging parents so she returned to Czechoslovakia. In 1970, she had to leave the university for political reasons. She started working in the National Heritage Institute in Prague as an art historian and in 1975, she became a specialised editor in the Artia publishing house. She collaborated with the Charter 77, distributed their texts, attended private lectures at the Havel’s house and at others. In 1979, she married Michal Jůza, in 1986, Mrs. and Mr. Jůza got a permit to work on their own and they started to make and sell stoneware. After the 1989 revolution, they started a publishing house as well. They closed down both the publishing house and the stoneware shop in 2018. They raised two adopted children.