The greatest art is not winning, but learning to lose

Download image

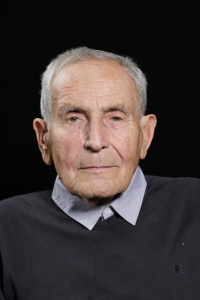

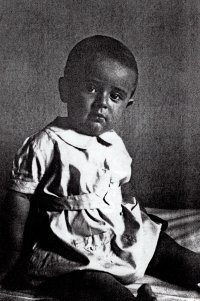

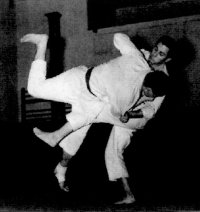

Jindřich Kaděra was born to Jan and Maria Kaděra on 6 September 1937 in a hospital in Zábřeh. His first memories relate to the unfortunate events of the Second World War and the liberation of Ostrava. Already in his youth he acquired a very positive attitude towards nature thanks to his activity in Junák. In 1952, he had to give up his scouting activities, both because he had to go to an apprenticeship in Opava and because of the growing repression of the scout movement by the communists. Jindřich trained as a universal turner at the Mining Apprenticeship of the State Labour Reserves No. 15 in Opava. There he learned about a newly emerging sport: judo. His first and only coach recognized a great talent in him and in 1954 Jindřich became the first junior champion of Czechoslovakia and right after that the national champion. After finishing his apprenticeship, he joined the Central Workshops in Ostrava-Privoz as a journeyman. In Ostrava, he founded a new judo team within the TJ Baník Ostrava, which he led until he entered compulsory military service. He enlisted in the Dukla Plzeň sports team. After his military service, he worked for a while in the Central Workshops, but for financial reasons he became a miner. First he worked in the Trojice Mine and later in the Paskov Mine. Despite the demanding work, he continued to represent Czechoslovakia in judo. His work in the mine was interrupted after twenty-six years by a spinal injury. After the Velvet Revolution, he helped found the Municipal Police in Ostrava and served as deputy director. In 2022, he and his wife lived in Ostrava.